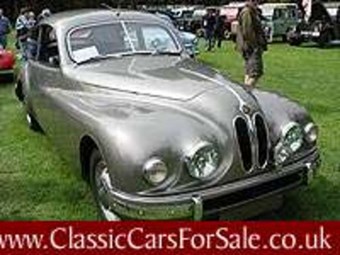

''Undoubtedly one of the great cars of our time'' wrote The Autocar in 1949, the year the new Bristol 401 coupe joined the 400. The prime appeal of the more popular 401 of course was, and still is, its flowing lines, a windcheating and distinctive new bodywork, created by Touring of Milan on their Superleggera principles, with lightweight construction of aluminium panelling over tubular steel framing, then welded to a chassis. With further wind-tunnel bodywork refinement by the Bristol Aeroplane Company at Filton, the combination of lightweight construction of just 2,700lbs and stunning aerodynamically efficient lines meant that the robust six-cylinder power unit, derived from the famous 328 BMW, had better top-end acceleration up to 100mph, making it one of the best performing cars of the period, with close-ratio gearbox and triple carburettors. Hand built at the rate of about 150 cars a year, using high quality aircraft materials, only items like tyres, wheels and carburettors were bought in. An exclusive car, priced at £3212.13s.4d, this was a truly expensive 'business express'. With effortless cruising, comfort for four and cavernous boot, features such as flush mounted push-button door locks and body-hugging bumpers are modern even by today's standards, the innovative one-piece bonnet hingeing either to the left or to the right, to choice.

PORSCHE 912 REVIEW

Porsche’s move upmarket when the 911 arrived in 1964 prompted concerns that Stuttgart had abandoned the more affordable end of the sports car market previously occupied by the 356C.

The manufacturer’s answer was to mate the earlier car’s 1.6-litre flat four with the Butzi Porsche-penned shell of its successor to create the 912. At £2,467, it was around £1000 cheaper than its six-cylinder sibling, and was praised in period for its handling and quality. While it was a hit in the US, its performance and price – it cost more than an E-type, and two-and-a-half times more than a Triumph TR4 or a Lotus Cortina – meant its success in Europe was limited.

Porsche dropped the 912 from its range in 1969 after 31,000 were sold, but in 1976 the name briefly reappeared in the US only in 1976 as the 912E. Only 2092 versions of this model – which mated the ‘impact bumper’ 911 body with the 914’s engine – is now one of the most sought-after 911 derivatives of all.

VITAL STATISTICS

ENGINE 1582cc/4-cyl/OHV

POWER 90bhp@5800rpm

TORQUE 90lb ft@3500rpm

MAXIMUM SPEED 115mph

0-60MPH 13.5sec

ECONOMY 25-30mpg

TRANSMISSION RWD, four-speed manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

1. When starting a 912 from cold make sure the lights for the generator and oil pressure go out immediately. The 356-derived four pot can take big mileages if it’s well looked after, but it’s prone to leaking oil around the oil cooler and rocker areas. A ‘sewing machine’-esque engine note is normal, but any excessive rattling or knocking could indicate worn bearings or camshaft issues looming.

2. Check the fuel lines carefully to see if they’ve been replaced, as original items – which in the earliest cars will be more than half a century old – will be perishing and prone to leaking. Leaving an original set of fuel lines unchecked is inviting an engine fire – it’s located almost directly above the engine fan, which will spray and leaking fluids right around the engine bay.

3. Inspect the VIN plate carefully, which is stamped into the bodyshell just behind the fuel tank in the front compartment. Unlike the riveted chassis plate – which can be found attached to the bonnet catch panel on the earlier models and on the right side front inner wing on the 912E – it’s difficult to tamper with and any signs of it being altered should prompt questions about the car’s identity.

4. A lot of cars have been imported from the US. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, as the climate in the dry states generally means these cars suffer less from tin worm, but check carefully for proof of servicing because there have been instances of US-market cars not being the same amount of TLC as cars originally sold in the UK.

5. Common corrosion sports include underneath the headlights, where water and debris has been thrown up by the front wheels, the lower edges of the doors where stone chips attack the paintwork and blocked drains allow moisture to build up on the inside, and around the top and rear of the rear wings, where clutter thrown up the rear wheels builds up.

6. The 912 was sold as standard with the 356’s four-speed manual transmission, but plenty of buyers paid for the 911’s five-speeder as an optional extra – both are pretty robust units, but check for any signs of whining or grinding during changes on a test drive. The 912E’s five-speed box – referred to in Porsche parlance as the 923 transmission - is unique to the car, but don’t let that put you off, as it’s identical in all but a few minor details to the 915 transmission fitted in post-1976 911S.

VERDICT

Anyone who tells you the 912 is the 911’s poorer relation clearly hasn’t driven one – it’s lighter than six-cylinder sibling and makes up for its lack of outright oomph with sweeter handling.

What it shares with the 911, however, is its crisp styling and wonderfully communicative steering, and while prices have risen in line with the wider classic market over the past five years they’re still, as a rule of thumb, cheaper to buy than 911s from the same era.

It’s comfortable, more than capable of cruising at motorway speeds and hugely enjoyable through the corners – and it’s much less obvious than its 911 counterpart.

BRISTOL 406 REVIEW

As the last of the six-cylinder Bristols before the advent of the mighty V8 cars, the rare and handsome 406 is a significant model that’s well worth seeking out...

It may lack the swoopy, aero-inspired lines of the earlier 401 and 402, but the 406 pushed Bristol into rarefied top level luxury car territory. It was bigger, heavier and more powerful than any previous Bristol, and – at close to £4500 – easily the most expensive. It wasn’t, however, all that fast, and struggled to break the all-important 100mph barrier.

It marked a sea-change in styling, too, with a new front sporting an open air inlet covered by a recessed mesh grille. But how does it stack up as a classic proposition today?

VITAL STATISTICS

BRISTOL 406

Engine 2216cc/6-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 105bhp@4700rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 129lb ft@3000rpm

Top speed 107mph

0-60mph 14sec

Consumption 23mpg

Gearbox 4-speed manual + O/D

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Being largely handmade, no two 406s are ever identical, but the key rot-spots remain broadly the same. The most common areas to require attention on unrestored cars are around the wheelarches. An electrolytic reaction can occur where the bodywork’s aluminium and steel sections meet around the arches, causing inevitable corrosion that must be cut out and replaced.

It’s a similar story with the battery and spare wheel floors, and while replacement is straightforward enough, being part of a coachbuilt car means it doesn’t come cheaply.

ENGINE

The 406’s 2.2-litre Type 110 engine – first seen on the export-only 406E – is a broadly strong and unstressed unit that should manage 100,000 miles before requiring a re-build. It’s worth paying more for a lower-mileage or recently re-built engine, however, as you’re looking at a bill for at least £10,000 to re-build a worn engine.

Contemporary publicity releases may have promised 100mph-plus speeds, but the reality was the car actually fell short of ‘the ton’ by a good two or three mph, despite having various innovations such as re-profiled pistons and a timing chain tensioner. Peak torque was developed at lower revs than previously, and the torque curve itself was much flatter, but early cars earned an unfortunate nickname, ‘tea kettle’, due to their propensity to overheating.

Sporting a steel block, the engine’s main weakness concerns its aluminium cylinder head – which is prone to corrosion – particularly around the water jackets and holes, and is known to warp. This latter issue has a knock-on effect on the head gasket – if the head is skimmed once too often following warping, the gasket can no longer maintain a tight seal between the block and the head. Thicker cylinder head gaskets are still available from Bristol, although repeated subsequent skimming will eventually lead to a new cylinder head being required.

RUNNING GEAR

The four-speed overdrive gearbox is pretty tough on the whole, although it’s not unheard of for the ball races to whine at tickover. If simply depressing the clutch makes the noise disappear, than replacements will be required.

The 406’s suspension, meanwhile, is unusual in that rather than relying on grease nipples, it uses a ‘one-shot’ lubrication system. This is operated via a plunger inside the car, which distributes oil to the front kingpins and rack-and-pinion steering.

Bristol recommends that the driver operates this system every 100 miles or so (and even more regularly in wet or muddy conditions), and failure to adhere to this regime can instigate blocked channels, or a non-return valve that jams in the open position. Ignoring this problem will obviously have consequences for the front suspension and steering, so it’s wise to check it works properly and that there’s no play in the kingpin and bushes.

INTERIOR

The 406’s interior was extremely luxurious when new, with sumptuous leather seats and high-quality bound Wilton carpets. Most of these items can be repaired in sections by experienced upholsterers, which is good news since a full refurbishment would involve non-original materials (exchange seats are not available) and a lot of money.

Wood features heavily in the 406’s cabin, and the section beneath the windscreen is exposed near-constantly to the sun, which eventually damages it.

Fascia controls and gauges are broadly reliable and long-lasting, but the oil/water gauges in particular can require work on higher mileage cars. Reassuringly, exchange units are still available from the factory, although they’re hardly cheap.

OUR VERDICT

Think Bristol, and many people immediately think either of 1950s aero-styled pioneers, or large, squared-off V8 saloons from the 1970s and 1980s. The 406 was very much a transition car and while it wasn’t particularly quick, it’s a rare, elegant, beautifully engineered and very luxurious tourer. They’re good value too, and enjoy an enthusiastic owner’s club following.

PORSCHE 914 REVIEW

By the late 1960s, Volkswagen needed to replace the Karmann Ghia, while Porsche was on the hunt for a new entry-level model. So when the two companies' bosses found common ground, a deal was struck.

The minimalist Porsche 914 pitched into a world full of ageing 1950s fins’n’chrome barges. To Volkswagen and Porsche directors at the time this modernity was a no-brainer.

Porsche racing success was culminating with the monstrous 1000bhp 917. It seemed that a mid-engined configuration was the way forward for road cars. Ferrari’s front-engined GT cars looked dated compared to Lamborghini’s Miura. Porsche wanted a car to replace the 356-motored 911-bodied 912, and Volkswagen was more than happy to back the proposal for a platform-shared, doublebranded sportscar.

It had to be practical, fun and make money for both firms. The four-cylinder VW version would be completed in Osnabrück by Karmann while the bodyshells, intended to become sixcylinder Porsche iants, were shipped to Zuffenhausen to be finished on the 911 production line.

VW boss Heinz Nordhoff had organised this along his usual terms with Ferry Porsche – a gentleman’s agreement to supply. But a scant six weeks after the first 914 prototype ran, Heinz died, on 12 April 1968. This blow to the 914 project meant the car had no single champion within either firm, and new VW boss Kurt Lotz decided VW had exclusive rights to the design he told Porsche that 914 bodies would have to cost more to cover the percentage of the body tooling costs. Much negotiation ensued. It ended when a new company was set up, each partner of which owned 50 per cent, although neither parent firm felt the need to drive the project along.

Power for the 914/4 came from the VW 411E. This unit was well-received, and actually put out about as much power as the 356 super 90 motor it replaced in the Porsche Canon, even though this one was built by Volkswagen. Sales in America were initially supported by the low-ish price. In the UK, the opposite story held for the lhd-only 914. Between January 1970 and June 1973 a total of only 242 914s came into Britain. And only 11 were the desirable 914/6 versions. Crayford converted some to right-hand drive – but at over £600, this conversion cost as much as a two-year-old Triumph Spitfire.

Ultimately, 118,927 914s of all types were built, with 115,597 of them produced as fourcylinder VW versions. That isn’t too shabby for a car vilified in Britain for being a flop. A flop? Porsche 356 sold only 76,500, and the Jaguar E-type only 72,500 after a production run more than twice as long. Porsche’s mid-engined 914 opened the door to the Fiat X1/9 and Toyota MR2.

Sitting on the ‘new for ’73’ Fuchs alloys this 2.0-litre car finishes the story of the 914. The post-1972 line-up deleted 1.7-litre four and 2.0-litre flat-six options. It had the revised 914/12 transmission, answering on-going criticism of the change-quality of the older gearbox. But all the 914 traits remain. Pull the opening flap to swing the door wide – mind your fingernails! Drop into the seat and the sparse design almost echoes around you. Yes, the car’s well-made. But in a VW-Porsche, the links to the people’s car are oh-so apparent. Remember that in Britain, this car’s price dictated comparison to similarly costly sporting icons such as a Jaguar E-type, not the MGB.

Yet to compare the car’s contemporaries is to miss the point. Fire up the clattery old boxer four and you’re reminded of the opening bars of Kraftwerk’s 22 and a half minute opus, Autobahn. And therein lies the car’s métier. For two people, there can be no greater car to economically cross the vast spaces of West Germany than this 2.0-litre Volkswagen- Porsche. Endowed with enough performance to give sporting thrills, the VW motor encourages you to drive it flat-out. Air-cooled motors produce bhp, not torque, so the car is thrashable and handles with such aplomb that no keen driver would refuse a top-stowed blast through Baia.

With the little motor wound up, the car lacks the punch of anything as sophisticated as a Lotus Europa twin-cam, But its everyman demeanor helps you drive the car daily, getting closer to its character with each journey. What initially appears as a muted lack of design reveals a cleverness – like an Austin 1800, there’s almost too much space, but the chic quality means that if you have to ask, you probably wouldn’t understand.

It may sound critical, but this car is a cerebral treat rather than visceral experience. The very useability of the car makes survivors rare – like many ’70s cars the build-quality was patchy and rot prevalent in the lower six inches. But pedal one hard, fling it into a tightening set of switchbacks and those skinny tyres grip on and on, the helm feeds back with minute messages of slip and grip to make any journey a treat.

On an open road this thing is fun to keep pressing on in. Soon you’ll be covering ground so rapidly that it’s hard to understand how such prosaic mechanicals translate into such a glorious – and unlikely – driving machine. Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 1971cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power 100bhp@5000rpm

Torque 116lb ft@3500rpm

Top speed 120mph

0-60mph 9.1sec

Economy 23mpg

Gearbox 5-speed manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

1. The 914 is an all-steel monococoque dating from the late 1960s, so like so many cars from this era, rust will be your biggest worry. Californian imports suffer less, but the later US safety bumpers are hardly things of beauty. Look behind the front bumper, and at the area around the torsion barr mountings on the bodyshell. Rust often affects the headlamp box below the pop-up lamps, and a blocked drain tube on the floor of the front boot leads to more problems. The front lid my have rotted at its rearmost corners, because the foam injected into the bracing members eventually becomes porous and holds water against the metal. Replacement is more cost effective than repair. Then check the scuttle just ahead of the windscreen, which is another common rust spot.

2. Check the seals of the targa roof and the quarter-lights for leaks. Open the doors and see if the GRP roof section can be fitted and removed easily. If the sills have been weakened, the car may sag in the middle, causing all manner of fit and finish issues. An outer cover on each sill is a common quick-fix, but they can conceal serious structural corrosion, so make sure you prod around at the exposed ends. Then lift the carpets to get a look at the inboard faces of the box sections and check the floor carefully where it meets them.

3. Damp in the footwells is common, and this leads to corrosion of the floor around the pedals and where the floor sections meet the centre tunnel. A seized brake pedal is one result: damp in the footwell causes the steel spindle to corrode and swell, and jam in its nylon bush mountings. Fresh air fan not working? It can fail because of cigarette ash falling inside the ashtray, and is generally sorted by cleaning. Exterior debris, such as leaves and road muck can burn out the motors. Door bottoms rust, and you should check the state of the shut face that carries the lock as well.

4. Next, look in the engine compartment behind the seats and check around the battery box for rust. Once started, it can spread backwards to the rear suspension mounting. Meanwhile, water and dirt accumulate in the rear suspension turrets, and the suspension leg will actually punch through the turret in particularly bad cases. Repairs are tricky and costly. Look, too, at the bottom of the rollover bar where an aluminium strip holds the vinyl trim in place; if the metal has rotted here, repairs involve removing the rear wings - which are welded rather than bolted in place. At the extreme rear of the car, check for rust in the boot floor, oftencaused by leaking tail light seals.

5. Engine maintenance is generally straightforward, although cars came from the factory with a fuel injection system and some DIY owners prefer to convert to carburettors rather than grapple with its complexities and costs. Experts reckon that a properly set u pinjection system is far preferable to carburettors, though, so make sure you've tried both before you go for a converted car. Dropped valves are a known weakness of these engines, as of other VW types of the period. Exhausts don't last well, either. Though the transaxle is a robust Porsche unit, driveshafts can fail, and their bolts can come adrift at the gearbox end.

6. The gear linkage on pre- 1972 cars isn't the best, and many owners have converted to the much-improved type that was introduced with the 2.0-litre models. It's a good precautionary measure to thoroughly overhaul the braking system and fuel lines when you take on one of these cars. The handbrake is built into the rear calipers, and can seize; the cable can also break. Note that brake dsics for the 2.0-litre models have a different offset from those on smaller-engined 914s, and the two aren't interchangeable. Fuel lines can rot through - especially in the area of the battery tray.

OUR VERDICT

Driver comfort is good and the mid-mounted engine gives wonderful handling. However, the rubbery-feeling gearbox can be tricky to use, and the ride is a bit firm at low speeds, although it does smooth out at speed. Go for a 2.0-litre model if you can, with its 120mph top speed and strong mid-range punch.

PORSCHE 924 REVIEW

The car that brought Porsche back from the brink of financial ruin impresses

Porsche AG stepped away from their usual air-cooled mid/rear engined configuration for the 1976 release of their new entry level model; the water cooled, front engined, rear wheel drive Porsche 924 2+2 Coupe. Built to replace the Porsche 914 and Porsche 912 (and itself replaced by the 944), the 924 was originally to be a Volkswagen, who commissioned Porsche to build them a sports car but never produced the design due to the oil crisis; opting to build the Volkswagen Scirocco instead. Instead Porsche bought the design back off Volkswagen in a deal that specified the car was to be built at a Volkswagen plant. This lowered the cost of production significantly for Porsche, making the car affordable to the public and as such it became one of Porsche's best ever sellers. Since the car was originally intended for VW showrooms, when released it was powered by VW's EA831 2.0LI4 engine mated to an Audi gear-box; this setup giving the car a respectable 125hp. With the success of 911 Turbo, Porsche decided to add a turbo-charged version of the 924 to their lineup to bridge the gap between the 924 and 911; which many Porsche dealers claimed was far too large. The 170hp Porsche 924 Turbo was released in 1978, however the car received poor reviews. Reliability was poor due to considerable over-heating and as such Porsche revised the model, releasing the 177hp Porsche 924 Turbo Series 2 in '81. Both standard and Turbo models sold well, prompting Porsche to release the race-inspired Porsche 924 Carrera GT at Le Mans. The Carrera GT was an aggressive looking car, with plenty of air intakes giving it purpose, and with 210hp it certainly had bite to match its bark. Success of the Carrera GT inspired Porsche to build more and more powerful versions of the 924; the 924 S (using a slightly detuned version of the 944's 2.5 litre straight four), the 245hp Porsche 924 Carrera GTS, the race-spec Carrera GTS Clubsport and the ultimate 375hp Porsche 924 Carrera GTR race car. Today, the 924 is still well provided for by dealers. There are also plenty of owners clubs who organise events, including the 924 Racing Championship run by Porsche Club Great Britain.

VITAL STATISTICS

Porsche 924S

Engine 2479cc/4-cyl/OHC

Power (bhp@rpm) 150bhp@5800rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 144lb ft@3000rpm

Top speed 135mph

0-60mph 7.8sec

Consumption 19.8mpg

Gearbox 5-spd manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

One of the biggest myths surrounding the 924 concerns its resistance – or otherwise – to body corrosion. Bar-room ‘experts’ will blithely tell you that all Porsches were galvanised at the factory, and therefore cannot rust, but this is only partly true. Cars built prior to 1980/1981 were only partially galvanised, so early models need care when it comes to checking for rust.

One of the most common 924 rot-traps is the area around the bottom rear corner of the front wings, where a bolt attaches the lower part of the outer wing to the floorpan. The battery tray is another weak spot, corroding through and allowing water to leak into the interior and fusebox, causing predictable electrical havoc.

It's worth getting underneath to check the condition of the fuel tank as replacing a rotten one is a time-consuming job that requires the transaxle to be dropped.

Being a Porsche, the 924 left the factory with resolutely consistent 7mm door panel gaps, so any significant deviation from this is likely evidence of a car that has suffered a shunt at some point. Also ensure the pop-up headlamps work and sit flush when lowered. Misalignment could be a sign of poor body repairs, while a failed motor can't be replaced and will need replacing.

ENGINE

The standard 924’s engine may be the least powerful, but it’s also one of the least troublesome, not least as it’s a non-interference engine, meaning a snapped cambelt doesn’t necessarily mean a detonated engine. However, changing the 924’s cambelt is relatively straightforward, so make sure it’s been done recently. Diligent owners will have replaced the tensioner pulley at the same time.

The 924S, introduced in 1986, retained the standard 2.0-litre 924’s narrow body, but gained a de-tuned version of the 944’s 2.5-litre ‘four’. Unlike the standard 924’s engine, this is an interference engine, so evidence of a recent (every 30,000 miles is ideal) cambelt change is a must. It’s a more complicated job, however, thanks to the need for a second belt, more pulleys and – if the job has been done properly – a new water pump, preferably one fitted with a metal impeller.

The Turbo is the most powerful of the 924 family (up 25bhp on the S), but also potentially the most problematic. The main issue is that the KKK turbo installation relies on the car being left to idle for a few minutes after a run to allow the turbo to cool. Switching the engine off immediately can allow the oil to reach boiling point and accelerate wear on the turbo bearings. Post-1981 cars were modified with improved crankcase breathing to help alleviate this problem, however.

Neglected servicing is your main concern as dirty oil and filters will accelerate valve-gear wear, and you need to ensure there's no exhaust smoke or signs of low oil pressure. And if a rebuild is required, bear in mind that many of the original Porsche parts - including valve guides, cam followers and engine mounts - are unavailable, so alternatives will need to be sourced.

The low-slung radiator can suffer stone damage, so check coolant levels and watch for signs of poor running as the induction system is sensitive to air leaks. Hot starting issues due to fuel vaporisation can be cured - and were sorted on later cars - but the Bosch K-Jetronic injection system isn't a concern otherwise. It's also worth checking the condition of the electrical harness servicing the starter motor and alternator - it runs close to the exhaust manifold and is prone to melting its insulation.

ELECTRICS

The top-model 300SE and 300SEL had air suspension, which was high-tech stuff for the early 1960s. The ride it gives is quite remarkable, but problems can be very expensive indeed to fix, and parts are not plentiful. Buy an air-sprung Fintail with your eyes wide open, and have the phone numbers of a specialist and your bank manager close at hand.

RUNNING GEAR

924 transmissions are reassuringly tough, but a leaky heater matrix (located directly above the clutch housing) will contaminate the clutch and shorten its life drastically if left untouched. A low whirring noise from the transmission tunnel on early 924s can be indicative of failed driveshaft bearings, which are pricey to fix, but an apparently broken clutch on a 924S might be nothing more serious than a collapsed clutch centre plate rubber damper. The standard 924 used much tougher coil springs.

BRAKES

Suspension-wise, normally aspirated 924s shared components with the VW Beetle and Scirocco, so parts can be found at a reasonable cost, although it is worth checking for any corrosion around the mounting points and for tired bushes and dampers. Neither the brakes nor steering give any cause for concern over and above general wear and tear, although it is worth inspecting the former for seizure due to lack of use.

INTERIOR

The cabin of a 924 is well screwed together, although the dashboard can suffer from cracks. They can be repaired, though, and secondhand items are reasonably plentiful.

As they are so cheap, now, 924s are popular with trackday enthusiasts. Given that preparation for these events usually involves little more than stripping out the interior, beefing up the suspension and fitting a roll cage, it’s not difficult to return a track car back to road-spec. Check for loose or ill-fitting trim, while neatly aligned bolt-sized holes in the floorpan may suggest that a roll cage might have been fitted at some point and later removed.

Electrical gremlins can besiege any indifferently-maintained 924. The switches that raise and lower the headlight pods, for example, are sealed, meaning failure involves replacement not repair. This in turn may have forced a cash strapped previous owner into resorting to bodges. A rusty battery tray can also allow water ingress onto the fusebox located directly beneath in the passenger footwell, while cold start and fuel pump relays are further common failings.

The Pasha seat material is available from European suppliers, but retrimming costs can soon mount, so don't ignore a tatty interior.

OUR VERDICT

No doubt about it: all 924s are now bona fide classics whose values can only increase from here on in, but if there’s one model it’s probably wisest to avoid as a general rule, it’s the Turbo. Yes, its performance is impressive, but the 924S isn’t that far short of its outright pace and its engine is much more tolerant of anything less than kid glove treatment. If you can be absolutely sure of a Turbo’s provenance, then go ahead, but otherwise, we’d look elsewhere.

Find a good example of the standard 924, and it will make a fine value first classic, but we suspect the lack of power will soon have you hankering after the greater poke offered by the S. As well as being more powerful, the 924S lacks the van-related stigma of the earlier car, and enjoyed a variety of modifications over the standard car. Of the three, it’s easily the best choice.

PORSCHE 944 REVIEW

Budget options aren’t usually as good as Stuttgart’s four-pot Porker

Anyone who tells you a proper Porsche needs more cylinders probably hasn’t spent enough time driving a 944. Yes, the acoustics aren’t quite as thrilling, but performance is sparkling – even without a turbocharger – and the handling is simply excellent. It won’t try to hurl you into the scenery in the same unforgiving manner as an equivalent 911, though you still need to be a bit cautious when pushing on.

Some early 944s lack power steering, but thankfully the later system doesn’t rob too much feel and does improve comfort.

Automatics are either something you like or don’t. With only three ratios, they certainly don’t sparkle in quite the same way when it comes to putting the power down.

VITAL STATISTICS

Porsche 944 S2

Engine 2990cc/4-cyl/DOHC

Power (bhp@rpm) 208bhp@5800rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 207lb ft@4100rpm

Top speed 140mph

0-60mph 6.7sec

Consumption 22mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Check the snout for accident damage. Being low, it’s prone to the odd knock and the fog lamps can get broken. Make sure the pop-up headlamps work. Engines are generally robust, but service history is very beneficial, and essential if the price is high. Timing belts need replacing every 48,000 miles but these days, the four-year interval is more relevant. The engine choice is 2.5 8v (Lux), 2.5 16v (S), 2.5 8v (Turbo), 2.7 8v (Lux) or 3.0 16v (S2). Power ranges from 150bhp to 250bhp for a Turbo S. Note that the 16v engines use a small timing chain between the camshafts – this needs replacing when the timing belt is done and pushes the price up. Expect to pay from £500 upwards for a belt change. Watch for head gasket failure too. Regular coolant changes are absolutely essential and often forgotten. Watch for exhaust smoke from Turbos.

Watch out for tired dampers causing a skittish or bouncy ride in the corners. Also check for evidence of track use. Worn balljoints and bushes all add up to sloppy handling. The brake calipers can suffer from corrosion, especially if a car has spent a lot of time sitting. Be aware of seized caliper pistons causing excess heat or a pull to one side. Use a (safe) emergency stop on a test drive to check.

It’s a myth that the 944 is rustproof, though panels were galvanised. Rot is now common in the sills, beneath the battery and at the bottom of the front wings. Repair work can run into the thousands, as more rot may be lurking under the surface. Replacement parts may not be galvanised, so check any repairs very thoroughly indeed. Check the flanks for signs of accident damage: panel fit should be exemplary. The sunroof should work and neither it nor the tailgate should allow water into the cabin.

The Turbo and S2 have an underskirt that sits beneath the rear bumper. Check the rear lights for damage, though second-hand replacements can be as little as £20. On Cabriolets, check the roof carefully for damage. Only 5000 Cabriolets were built. Make sure the roof operates correctly and that it is not damaged – a replacement is likely to be around £500.

ELECTRICS

Make sure all electrical equipment works, including front and rear wipers, electric windows and the sunroof. The roof uses quite a complex mechanism, so fixing it isn’t easy and could have an impact if you decide to resell.

RUNNING GEAR

The gearbox is mounted at the rear so while a sloppy linkage isn’t tricky to sort out, check that the clutch has good bite. As you release the clutch, you may hear a rattling which is usually the torque tube. These can get noisy but failure is thankfully rare. The Volkswagen-sourced automatic gearbox is also tough, but watch for gears slipping or excessive noise: it could be a rubber-webbed flexplate breaking up and that’s a £1200 part.

Watch for dubious exhaust upgrades. Stainless steel is often seen as a wise move, but sports systems can be excessively noisy. What seems fun on a short test drive might be a considerable pain in the ear on a long journey. Fuel lines can corrode and proper Porsche replacements cost £1000 to fit as the subframes need dropping. Using flexible pipe can be a lot cheaper, but may upset the purists.

BRAKES

What condition are the wheels and tyres in? Are there signs of kerbing or unusual wear? Matching tyres from a reputable brand are a good indication of diligent ownership. A history file that includes a recent alignment check is encouraging – tyres that are worn along one edge less so. While the front suspension uses coil springs, the rear uses torsion bars. These can occasionally require re-indexing – where you reset the ride height – but not often.

INTERIOR

Cloth trim can deteriorate with time, though you may be able to source decent second-hand items for not too much outlay. But that situation is unlikely to last.

OUR VERDICT

If going ridiculously quickly isn’t the most important thing, you can have a lot of fun in a 944 LUX. They’re brisk and enjoyable. Turbos seem rather over-valued for our liking, though they are undeniably quick – 5.5 seconds to 60mph. The S2 is only a second behind though, and arguably much more drivable in real world circumstances. The torque on offer is staggering thanks to one of the largest capacity four-cylinder engines of the past 40 years.

PORSCHE 968 REVIEW

A substantial part of the 968’s appeal concerns its styling. For what is, in essence, a heavily re-worked 944, the 968’s colour-coded tail-lights and aggressive 928-alike exposed pop-up headlights give it a startling resemblance to its V8-engined GT big brother.

For something that delivers not far short of minor supercar performance and handling, the 968’s build quality is outstanding, too. Doors, even on the Club Sport, close with a comforting dull thud, and interior trim and minor controls and switchgear feel like they’ll last forever.

They’re mechanically tough, too, with the few weak areas (gearbox bearings, camshaft chain drives) coverable on a reasonable budget if you buy wisely, and adhere strictly to recommended service and repair intervals.

These are practical and while the transaxle means the boot is shallow, only the CS lacks rear seats.

Which should you choose? The standard 968 is a GT car and the Club Sport much more hardcore and driver-focused. The Cabrio is more of a cruiser.

It’s instantly clear that all 968s were designed specifically as proper sportscars from the moment you settle into the driver’s seat. The steering wheel is just about perfect in terms of size and weight and the position of the short-throw stubby gearlever is similarly spot-on. The minor controls have often been likened to boiled sweets scattered across the dashboard at random, but everything feels engineered not merely constructed.

All 968s use the same 3.0-litre engine and rack and pinion power-assisted steering, but the lighter Club Sport feels the most alive and has genuinely electric responses thanks to its higher power-to-weight ratio (180bhp per ton compared to the standard car’s 169bhp per ton).

And yet, 240bhp in something that, even in its most opulent guise, weighs only a smidgeon over 1400kg is always going to feel seriously quick. Factor in super-responsive steering, old fashioned rear drive and a front-rear weight distribution that’s not far off 50:50, and you’re left with a car whose heart and sould is pure sportscar. You’ll love it!

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

1 It’s almost unheard of to find any 1990s-era Porsche suffering from body corrosion; all 968s were galvanized at the factory, so even untreated stone-chips on that low-slung bonnet shouldn’t fester. Evidence of rust, then – even now that the cars are well out of their 10-year anti-corrosion warranty period – is almost certainly going to be as a result of heavy accident damage that’s been repaired inexpertly using pattern parts. Given that these cars are popular with the trackday fraternity, such damage is likely to have been substantial, too. Having said that (and rather curiously) one known 968 rot-spot is around the windscreen – leaking rubbers can instigate bubbling around the entire screen.

Owners also need to be aware that the galvanize acts as a sacrificial membrane, so as 968s age, they will corrode in the same places as older 924/944 siblings: sills, arches and battery tray.

2 The 2990cc engine is modified from the preceding 944 S2’s engine, and was therefore at the very peak of its extensive development by the time of the 968’s launch. Major problem are rare, then, although anything less than utter turbine smoothness indicates potentially expensive problems with the balancer shafts. Also watch the VarioCam system, which is controlled by Bosch’s proven Motronic engine management system. Its intentions are all good – chiefly to maximize fuel efficiency and reduce emissions from the twin-cam engine, but it also improved torque slightly – but if the chain drive that runs between the camshafts stretches – or worse, breaks – then you could be looking at a repair bill comfortably in excess of £1000. Evidence that the camshafts, tensioners and guides have been replaced every 75,000 miles or so (and the chain drive every 30,000 miles), is a big selling point.

3 Both of the available transmissions – a six-speed manual and a four-speed Tiptronic automatic with clutchless manual override – are bank-vault tough. Slop indicates that the dual-mass flywheel hasn’t long to live. More seriously – and more expensive to rectify – the manual gearbox’s bearings are susceptible to over-adjustment, and excessive wear will make its presence known by a loud noise accompanied by drivetrain judder both under load and power lift-off. Replacement is possible, but it’s a gearbox-out job, and therefore hugely expensive – bank on at least £800.

4 The 968’s suspension comprises front wishbones and MacPherson struts allied to gas-filled dampers, plus semi-trailing arms and torsion bars out back. Anti-roll bars are fitted front and rear. None of these components has a particular Achilles Heel, although the enthusiastic driving style that these cars encourage will inevitably accelerate wear to bushes, wishbones and balljoints, with a resultant feeling of sloppiness in driving feel. On Club Sports specced up with the optional M030 Sport Pack, adjustable Koni dampers set to their hardest setting suggest extensive track use, since the pack also comprises stiffer springs and roll-bars, and the CS warranted a 20mm lower ride height as standard anyway.

5 Brakes are similarly robust on these cars, although don’t be surprised to find that the brake calipers require a complete re-build every 18-24 months – corrosion eventually causes the plates that hold the pads in position to lift.

6 The 968’s interior is impressively hard-wearing. Aftermarket racing seats should start alarm bells ringing, but the Club Sport’s fiberglass Recaro seats are as comfortable as they are supportive. Standard chairs were available as a no-cost option but they added 17kg. Dashboards can be prone to splitting.

OUR VERDICT

Think ‘classic Porsche’, and everyone tends to think 911, but when was the last time you saw a 968? This must be due in part to the car’s relatively short life (just four years in total for right-hand drive models), but we suspect still more people dismiss it as being little more than a short-lived, warmed-over 944 S2.

And that’s a pity, because the 968 is a truly great car in its own right. The standard 944 may be more GT than GTI, but the Sport and Club Sport offer grown-up Porsche performance and driver involvement way beyond the budget spent.

Cars that have been cherished are proven to be mighty reliable, build quality is exceptional, and there’s even a degree of practicality. Replaced by the less macho Boxster in 1995, the 968 is one of the classic car world’s best-kept secrets. Don’t let on.

PORSCHE BOXSTER 986 REVIEW

Can’t quite afford a 911? Opt for a Boxster instead and you won’t be disappointed

Boxsters provide a comfortable driving position for both short and tall drivers, thanks to an adjustable-position steering wheel and decent seat adjustment. Once settled in, it quickly becomes apparent that the chassis and steering are so good that the Boxster can seem underpowered at times, especially the base 2.5-litre model. It blooms when being driven at the upper and outer edges of its performance envelope, easily making you laugh out loud with pure pleasure! The exquisite noise emanating from behind your ears makes you want to send the tachometer’s needle into the upper ranges again and again, as the flat-six’s ethereal wail really comes on song around 5000rpm. The car dances around country lanes, its nose responding to even the smallest inputs, the brakes so finely judged that you’ll found yourself left foot braking in time - a dab to tuck the nose in, unwind the steering and then nail the power. A good Boxster drives like a Porsche should then, and feels solid, just like a Porsche should.

VITAL STATISTICS

1996 Porsche Boxster 2.5

Engine 2480cc/6-cyl/DOHC

Power (bhp@rpm) 201bhp@6000rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 177lb ft@5000rpm

Top speed 155mph

0-60mph 6.4sec

Consumption 29mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Park the car on level ground, then start the exterior examination by checking for signs of body damage or accident repairs. Corrosion is easy to spot as the paint will have bubbled and/or cracked. Measure the body panel gaps, particularly around the front and rear luggage compartment lids and the doors. If the gaps are even then chances are the body is straight. Major inconsistencies in gaps indicate the car has been poorly repaired after an accident.

ENGINE

Engine access is complicated, but it’s possible to carry out a basic inspection of the top of the engine. Look for obvious signs of oil, coolant and power steering fluid leakage. A known Boxster issue is failure of the engine’s rear main seal – a giveaway sign being when oil begins weeping from it. Owners usually keep an eye on the oil level and get a new RMS fitted when the car is having a clutch change or service, but if you’re viewing a car with a weeping seal, then factor this into your thinking when haggling on price.

ELECTRICS

Check around the combined headlight and indicator assemblies for cracked lenses and stone chip damage. You also need to grab a torch and peer through the front spoiler to assess the condition of the front mounted radiators. The excellent aerodynamic design of the Boxster is fantastic at drawing cooling air through the radiators, but the downside is that it also acts as an enormous vacuum cleaner, sucking up anything it can from the road surface. Make sure the radiators are clear of debris, as organic materials will decay and cause corrosion issues as the car ages.

Remove the plastic battery cover in the centre of the front luggage compartment and inspect the battery for condition and any evidence of acid spill and/or corrosion. Examine the compartment’s panelled areas for moisture damage and staining – if everything is clean, what lies beneath is probably in decent nick.

BRAKES

Check the brake discs (rotors), callipers and pads. Pad friction material must be greater than 2mm, and the discs must be free from damage or surface rust. Look for evidence of fluid leaks over any components in the wheel wells, including at the rear of each wheel.

INTERIOR

Inspect all interior fittings and assemblies, including assessing the condition of both seats, ensuring none of the trim is cracked, torn, faded or missing. Check all electric seat functions are working correctly, especially heated seats. A cracked dashboard is extremely expensive to repair. Run the electric windows up and down to see if there’s any moisture trapped within the door.

OUR VERDICT

The Boxster phenomenon didn’t happen by accident. Porsche has long understood the importance of component sharing, ever since the strategic revolution that transformed the company’s corporate fortunes in the mid-1990s. The original 986 Boxster was the first Porsche to prove the value of that concept, sharing much with the 996-generation 911. The Boxster was an immediate hit, and ever since has maintained an intimate relationship with the 911, while contributing strongly to Porsche’s bottom line.

Mixing almost perfectly resolved handling with serious performance and appealing value for money, the original Boxster’s status as a fully-fledged, envy-of-the-class Porsche sports car now seems indisputable. Grab one with the optional hardtop and you’ll be able to use it all year round too. Best of all, you can bag a decent example with full service history for as little as £5k today. What are you waiting for!

RELIANT SCIMITAR REVIEW

With power, style and poise, we discover that life in plastic is fantastic

With the Sabre Six beginning to look long in the tooth by the early 1960s, a replacement was on the cards. It was fortuitous then, that Ray Wiggin, Managing Director of Reliant, chanced upon an Ogle SX250 at the 1962 motor show. Made from GRP and echoing the lines of the Daimler Dart, it was exactly what Reliant was looking for. Two years later, the design was adapted to accept the chassis and running gear of the Reliant Sabre, along with a Ford 2.6-litre engine, before being unveiled to the market in 1964. Lusty, powerful and handsome, it received good reviews from the motoring press.

VITAL STATISTICS

RELIANT SCIMITAR GT SE4

Engine 2553cc/6-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 120bhp@5000rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 140lb ft@2600rpm

Top speed 117mph

0-60mph 11.4sec

Consumption 23mpg

Gearbox 4-speed manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Unusually, the SE4’s bodywork was made entirely of GRP. While this means rust will be less of a problem compared to its rivals, it does throw up its own set of problems. Plastic tends to flex a lot more than steel, so paintwork should be your first point of inspection.

Cracking is common on cars that have been poorly re-sprayed. Split or flaking paintwork is bad news and could be the result of a half-hearted repair. If left exposed to sunlight or extremes of temperature, bodywork can warp. The best way to check this is to have it driven away from you. If it looks a bit uneven or crabs sideways then tread carefully – it can cost a fortune to put right. Similarly, be wary of cars that require a repaint – a decent job can be prohibitively expensive.

ENGINE

The 2.6-litre, four-cylinder engine used in the SE4 was sourced from the Ford Zodiac (but with the addition of triple SU carburettors) and is a strong and reliable unit, providing it is well cared for. Ensure that oil and coolant levels are adequate and check the history file for evidence of regular servicing. The engine uses a cast iron head in an overhead valve arrangement, so tappets are easily set. Be more concerned by any knocking noises or blue smoke under acceleration. White smoke under load is bad news as well, and suggests that water may be mixing with the oil due to head gasket failure. Check the oil filler for mayonnaise and the header tank for an oily film. Check too for an up-rated cooling fan and allow the car to heat up, making sure that the thermostat kicks in. If this doesn’t happen, then assume the car has overheated recently. Coupés rarely overheat, but when they do it is usually a result of poor maintenance and a damaged radiator.

RUNNING GEAR

The suspension and running gear is simple but effective, utilising coil springs and wishbones at the front and coil springs and trailing arms at the rear. Front suspension has a tendancy to drop, so make sure the car appears to be sitting level. Rear dampers tended to wear out quickly in early cars, but this problem was addressed in cars built after October 1965. Girling discs at the front and drums at the rear were spongy, even when new, so don’t let this put you off. Watch for any juddering under heavy braking, as front discs can warp if put under too much stress. Check that the steering doesn’t seem too heavy, it can be a sign that the trunnions haven’t been greased regularly.

Take the car up to speed and make sure the overdrive is functioning properly – cruising can be a chore without it.

INTERIOR

Many of the interior and electrical components were cannibalised from other models, so don’t be surprised to see a mish-mash of parts that don’t quite fit. The sun visors actually foul the rear-view mirror when you pull them down.

Early cars will have a headlamp dimmer switch on the floor – check this hasn’t been damaged,.

OUR VERDICT

When you think of 1960s British sports cars, the Scimitar SE4 is probably not the first model to come to mind – which is exactly why they have such a committed following today. Always an uncommon car, the SE4 is now genuinely rare. As long as you are aware of the costs involved, there’s no reason to be scared by a project. Spares are easily available.

BMW E9 CSL REVIEW

The 3.0 CSL was BMW’s first truly sporting coupé to match looks with performance, style with desirability.

The timeless shape of the big BMW coupé was first seen as far back as 1965, with the 2-litre coupé by Karmann. It developed into the E9 chassis in 1968 and production continued until the final model rolled of the production line in 1975. By introducing a coupé in 1968, BMW signalled the intention to return to the luxury car market sector, an area it had been forced to ignore for years while it struggled to turn around its fortunes during the 1960s. Early cars ran on carburettors, until the adoption of Bosch fuel injection in the 3.0 CSi.

A turning point in BMW’s motor sport history was the introduction of the homologation special CSL, which stands for Coupé Sport Leicht. The new model offered little in the way of luxury equipment, weight saving being the order of the day. This was achieved by using thinner gauge steel in the construction of the body, along with an aluminium bonnet, boot and doors.

To qualify the car for racing in the Over 3-Litre division, the engine was rebored to give a capacity of 3003cc, which in road trim resulted in almost 200bhp. The CSL label only required the production of 1000 cars to make it eligible to race. It was developed by a separate division in BMW AG, which would go on to become BMW Motorsport GmbH. While the CSL does not carry the M badge, many unofficially consider this to be the first-ever ‘M’ car.

The 3.0 CSL proved to be an astonishingly durable racer. Such was its longevity in international racing, it was on the grid every year from 1972 through to 1978. Even more impressively, after its success in 1973, 3.0 CSLs won the European Touring Car Championship every year between 1975-1979. By this time, the old warhorse was getting somewhat long in the tooth, meaning that it was finally put out to pasture.

Only 765 roadgoing LHD CSLs were built between 1972 and 1975, with just 500 RHDs produced in that time. Nearly all of the latter had additional equipment over the LHD, to help aid the driveability of the car on a daily basis. These optional extras were grouped and labelled the City Package, and included electric front and rear windows, power steering, interior bonnet release, chrome CSi front and rear bumpers, and a tool kit.

The rarity of both of these versions has ensured that they are much sought after today. Prices will rise in the future.

With Bosch D-Jetronic mechanical injection, you don’t need to worry about a choke when rousing the BMW 3.0 CSL. The engine starts keenly and pulls hard and sure, even from cold. Need a burst of acceleration? It’s accompanied by a metallic thrum that speaks of lusty refinement. There is a real tingle of competition in this car’s genes. And the way the CSL gets the job done can’t fail to impress.

Brawny yet sophisticated, it’s hard to imagine a more suitable steed in which to cross continents or rack up some heavy-duty mileage. A long-distance cruise down through Europe to the warmth of the Mediterranean would be right up the CSL’s street. Few cars you’ll drive have such a crisp and responsive engines – it seems to thrive on hard work, yet the airy cabin manages to be restful.

The suspension is equally inspiring. When driving over larger bumps or less than smooth roads, the CSL demonstrates an impressive ability to soak up undulations. The damping mostly makes an efficient job of preventing excessive pitch and float.

It’s game for some fun, too. When setting up for a long sweeping bend, the cornering characteristic of the CSL is predominantly one of stable, predictable understeer. Nothing too excessive but, at the same time, just enough to keep the nose from wandering off-line. Flicked through a tight turn in low gear, the big coupé will hang its tail out in a highly satisfying manner, like the true thoroughbred it is.

In between the two extremes, you can stimulate a nicely balanced, neutral style of handling. The slim steering wheel gives an impression of quicker steering reactions – you simply think it through a bend. The fitment of a limited slip differential is a worthy step, helping to improve traction significantly on slippery surfaces.

Naturally, in wet weather, it is much easier to get the rear wheels spinning, so a certain amount of sensitivity is required when moving off briskly or cornering under full power as both rear tyres spool up and launch the lightweight car forwards. Once it has warmed up, the ventilated disc brakes prove more than up to the task – you’ve got no bother hauling 1270kg of Beemer to a halt on demand and within a reasonable distance.

As a 3-litre coupé with elegant styling, refined running and decent acceleration, the CSL is difficult to match. It has delightful road presence which conspires to flatter any driver. Admiring glances come naturally and respect on the streets is guaranteed.

RENAULT 5 GT TURBO REVIEW

Can’t afford an original R5 Turbo? Happily the Phase 2 GT Turbo offers similar thrills at a fraction of the price. We find out exactly how to bag yourself a good one

The GT Turbo isn’t just a fierce engine stuffed into a shopping car chassis – Renault really went to work on the suspension too. This is a superb handling car, especially the way the front end just dives into corners and then feels nailed to the road.

Sometimes, it’s almost as if it grips too much. At the point where you’re expecting to turn the wheel more to get around a bend, the car actually digs in harder, forcing you to wind-off lock.

Anyone who’s ever driven a Clio 172, or its descendants, will recognise the way the GT Turbo behaves. Add in a sweet, slick gear change and the GT Turbo is a mighty slice of old fashioned fun. It’s one of those rare cars that are incredibly easy to drive hard. The ride is more composed and gentle on Phase 2 cars, which makes the GT Turbo a usable car on the road as well as the track.

It has the desirable qualities of all great hot hatches – it’s exciting, addictive and spurs you into driving it harder.

VITAL STATISTICS

1987 Renault 5 GT TurbO

Engine 1397cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 118bhp@5750rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 122lb ft@3750rpm

Top speed 120mph

0-60mph 7.3sec

Consumption 28mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

The metalwork on these cars is really thin, so look for any covered damage. Wonky panel alignment is fairly common as a result. Regular R5 rust spots are numberous and include along the bottom of the front windscreen, rear window rubbers, rear wheel arches, wings, tailgate, doors and floorpan. Also examine the outer sills, behind the plastic sill extensions, the inner sills and the front jacking points. Other common rust spots are the front and rear bumper mounting points.

ENGINE

The 5 Turbo’s pushrod 1397cc engine is prone to noisy tappets, but this is not something to be unduly worried about. Of more serious concern is a noisy camshaft – evident as a slightly deeper sound than the tappets. This noise means the camshaft is worn and it won’t be long before you have to replace it, an expensive task that involves removing the head itself. An engine that has been serviced regularly and maintains a good oil pressure should easily manage 150,000 miles before rings, main bearings or valve guides need replacing.

On the test drive, be sure to find a series of left and right turns. While going round the corner, listen out for a knocking noise coming from the opposite side you are turning into. This noise indicates a driveshaft in need of replacement. When driving along at about 30mph in fourth gear, open the window and listen for a knocking noise coming from the engine. This is the big end bearings knocking and if you do hear this, then walk away from the car, as a full engine rebuild will be required imminently. Make sure that the car does not misfire when on boost – this could simply be down to incorrect ignition timing or a more serious engine fault. The key to reliability is in accurate fuel set-up, and using super unleaded fuel to prevent pre-detonation. Check what boost is being used and ask lots of questions about how the fuelling has been set up.

RUNNING GEAR

When switching on the ignition, make sure that the oil light, battery light and handbrake light come on, and that the oil pressure gauge shoots up. This acts as an oil level reading until the engine is switched on and then it turns into an oil pressure gauge. When you start the car, make sure that the oil pressure gauge moves up and down with the revs. If the pressure gauge is sitting flat on the bottom of the gauge then it either means there is no oil pressure and that the head gasket has gone, there’s something major internally wrong with the engine, or the gauge is simply not working.

Check that all the electrics inside work as French cars of the 1980s/1990s don’t have the best reputation in this area. The R5 uses a chemical sealant in the front windscreen – they are known for coming away from the rubber because of movement in the A-pillars, so when inside the car gently push the windscreen to see if it moves.

INTERIOR

Interiors are generally hard wearing, but the driver’s seat outer side bolster foam breaks down. New bolsters are still available from Renault, but cheaper replacements can be found easily enough secondhand. If the front seats rock excessively on their mountings, check the two pivot bolts that couple them at the front to their sub frames, as they come loose and can need tightening from time to time. The electric windows are known for being slow, caused by the motor’s old dried-out grease and perished rubber guides. Some time spent cleaning and re-greasing the mechanism can vastly improve things. However, sometimes the cause of the slow windows and central locks is simply corroded electrical connectors. These fail to pass adequate current to operate the motors and replacement for new is required as cleaning has little or no effect.

OUR VERDICT

The Renault 5 GT Turbo is a rare beast on UK roads, so finding one will be difficult and finding a good one even harder. Certain parts are now scarce, meaning they can be very expensive. The simplest advice is to buy the best example your budget will allow, as the cost of refurbishing a duff car is likely to be significantly higher than the price you’ll pay for a decent one in the first place. These cars are still prime targets for thieves, so you’ll definitelty want to look into an upgraded anti-theft system, if this hasn’t been done already. The GT Turbo is a highly usable car, definitely capable of daily driver duties as well as weekend blasts.

BMW M535I REVIEW

BMW's press pack maintained that the BMW E12 M535i set a new standard in understatement and that it offered the restrained dignity of a Savile Row suit.

What Car? magazine called it the ultimate boy-racer's car and about as retrained and dignified as a gold lace stage costume. At £13,745 new in 1981, it must have been intended for a rich boy racer! Developed by BMW's Motorsport subsidiary, this exclusive 140mph model combined performance, comfort and tractability in traffic, offering pure excitement. Its 3,453cc twin-cam power unit developed 218bhp at 5,200rpm and a sizeable 228lb ft of torque, 60mph coming up in 7.1 seconds and 100mph in 19.8 seconds. BMW's first M-pack offering, just 200 RHD examples were allocated in 1981.

In 1985 the E28 M535i arrived, offering 218bhp and an even more outrageous bodykit. There were some suspension tweaks over the 'normal' 535i, and a hefty price premium. The E28 has gone through the hooligan's banger stage and the few that have survived are now highly prized.

RENAULT 5 MK1 REVIEW

Finding one may be the hardest thing, but it will be worth it. We are your guide to the charms and practicalities of owning a Renault 5

The Renault 5 pretty much set the template for the modern supermini and quickly spawned a raft of imitators, including the Ford Fiesta. A combination of chic styling and hatchback practicality attracted over five million buyers – and, if you like the looks, you’ll be equally impressed by the way an R5 goes down the road. Sporty Gordini and Turbo models aside, modest power outputs mean performance is only average but it feels sprightlier than figures suggest.

We’d recommend one of the larger power units, since all offer good economy. Like many French cars of the time, the 5 benefits from soft, long-travel suspension that allows it to glide over urban ruts and potholes – it’s far more comfortable than many other small car offerings, although the penalty is alarming body roll on faster corners. You do get used to it and can soon make the most of the accurate steering and light controls to best enjoy the limited power.

Early cars’ dashboard-mounted gearshift takes

a little more getting used to; the later floor-mounted lever is light and accurate. Another R5 plus point is the interior – it’s somewhat spartan in early incarnations but roomy enough for family duties even if the rear seats are a little tight for the long-legged. The dashboard is logically laid out with easy-to-reach switches located around the instrument binnacle on later models, and just enough dials and warning lights to keep you informed.

The driving position is quite upright but is none the worse for that and most people should be able to get comfortable behind the wheel. It’s worth noting, though, that space in the footwell is a bit tight for larger feet. The R5 is refreshingly honest and fun though, and that’s good enough for us.

VITAL STATISTICS

(based on Renault 5TL)

Engine 1108cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 45bhp@4400rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 63lb ft@3750rpm

Top speed 86mph

0-60mph 20.6sec

Consumption 45mpg

Gearbox 4-spd manual

HAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Later cars received better protection but rust is still common on the R5. Check the top and bottom of the front wings (including inners), the bottom of the doors and tailgate, and the leading edge of the bonnet. Examine the rear wheelarches, the sills, front and rear screen surrounds, and the areas around headlamps and fuel filler.

Bubbling under the vinyl roof on later models should be treated with suspicion, and the plastic side cladding can also hide rot. A check of the floorpan is advisable too, especially around the rear suspension mounting points as sill corrosion can easily spread. Finding a complete, solid example is key with the R5 – replacement panels (indeed any exterior trim parts) are incredibly hard to source so restoration is unlikely to be easy.

ENGINE

Engines ranged from an entry-level 845cc ‘Ventoux’ unit through to various larger capacities up to 1.4 litres. The bigger engines were dubbed ‘Sierra.’ All are fundamentally sound if treated to proper maintenance. Alloy cylinder heads mean correct antifreeze levels are vital for longevity – check the whole cooling system as corrosion and leaks lead to overheating and inevitable head gasket failure. Rattling valve gear and perished valve stem oil seals that cause smoke on start-up are issues to watch for. Turbocharged Gordini engines will need extra care – blown turbo plumbing is an expensive fix.

ELECTRICS

Check the electrics. The wiring between body and tailgate is a weak spot and can lead to inoperative lights.

RUNNING GEAR

A four-speed manual gearbox was standard – five-speeders arrived later – and apart from whining bearings or worn synchromesh, should be trouble-free. An obstructive dash-mounted gearlever on early models is most likely a worn linkage – easily sorted. A floor-mounted lever was optional from 1975 and standard from 1978. A three-speed automatic arrived in 1979. Listen for clicking CV joints and check the clutch isn’t slipping – replacement is fiddly as the steering rack sits on top of the forward-mounted gearbox and must be removed before the gearbox can come out.

BRAKES

Wear in bushes and joints apart, the rack and pinion steering is usually trouble-free, and the same goes for the brakes. Most R5s got a disc/drum set-up – early models were drums all round, though Gordini Turbos got discs all round – and basic maintenance will keep things healthy. Note that the handbrake operates on the front wheels on Ventoux-engined cars.

Suspension is by telescopic dampers and torsion bar springs at both ends. Upper and lower front ball joints wear quickly, and you’ll need to check for rot in the torsion bar mounting points and those for the rear trailing arms. The bonded rubber bushes for the latter are now available from France. Wheels on all models used a three-stud fitting with some cars getting alloys as standard – check them for pitting and corrosion.

INTERIOR

Pay attention to trim condition. Original fabric is unavailable and the foam can disintegrate, leading to saggy seats. Damage to dashboard or doorcards will be problematic, too, as replacement interior trim is extremely scarce.

OUR VERDICT

They may be very rare now but there is plenty to like about this fine-riding French hatchback. The comfortable interior and solid mechanicals add to the attraction, making this a fine choice as a small, but stylish, classic. Corrosion worries and lack of parts availability are concerns though, so you’ll need to buy carefully. Find a good one, and you won’t regret it.

BMW 3-SERIES E30 REVIEW

The 3-Series E30 is the Swiss Army Knife of classic motoring: it fits right in at shows, tackles trackdays with gusto and takes on the daily commute with aplomb.

For many years the E30 has been the classic of choice for those with a more enthusiastic driving style, especially the 325i Sport models with their limited-slip diffs.

E30s are hugely popular when it comes to amateur motorsport. One of the main reasons for this is that the rear-wheel drive/front engine format is perfect when it comes to learning how to control a car on a circuit. 1.6-litre, 1.8-litre and 2-litre cars all seem fairly pedestrian in the speed stakes, but all of them will be a barrel of laughs when pushed through the bends. The standard 325i offers the best bang for your buck, producing 169bhp out of the box. A 325i can be bought for as little as £1500.

A decent E30 really is a joy to drive. The suspension is firm enough to hold the car when pushed hard, but soft enough to iron out the bumps on a longer cruise. Oversteer is easy to provoke, however many a decent driver has been caught out in the past, so be careful.

VITAL STATISTICS

1986 BMW 325i

Engine 2494cc/6-cyl/SOHC

Power (bhp@rpm) 169bhp@5800rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 167lb ft@4000rpm

Top speed 138mph

0-60mph 7.2sec

Consumption 26mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

The car may look clean, but rot hides itself very well in E30s. Sills, scuttle and arches are the main problem areas. Feel around behind the front and rear arches for crustiness, especially if the car looks freshly undersealed. Inner wings will go behind the front wheel arch guard so open the bonnet and check for rust along the top edge of the inner wing. Front suspension turrets can rot from the base. Check for rust on the bulkhead by removing the fuse box. If you find rust here walk away.

Open the boot and remove the jack. If there’srust here it will have made its way from the rear inner wheel arch. Also take a screwdriver and magnet to the sills. Lift the carpets in the boot and footwells. Rust here will be difficult to cure. Be wary of sunroofs too. Rot in the roof skin is terminal, so watch out for bubbling here.

ENGINE

E30 engines are well known for their reliability, but only if well maintained.

A fully documented service history is a must. The cambelt should be changed every 60,000 miles or at four year intervals. If this isn’t documented, budget to have it done as a matter of course. Start the engine from cold and listen for noisy tappets. If the sound continues when warm then they need to be adjusted. Valve clearances should also be set every 15,000 miles. Improperly adjusted valves can break rocker arms.

Check oil and coolant levels. Look for signs of oil in the coolant and mayonnaise around the oil filler cap. Both could suggest head gasket failure. Carry out a compression test before buying. Allow the car to idle until warm listening for the fan to come on. If it doesn’t, then assume the car has overheated so warping the cylinder head.

ELECTRICS

Check the engine bay. Make sure the colour matches the exterior of the car. Fresh paint may suggest the car has been in a crash, so make sure you ask all the right questions. Ensure you get a HPI check. Due to the low book value of E30s many crash-damaged vehicles are written-off as a result of what most would consider light damage. There are a lot of decent-looking cars on the road that have been registered as Cat C or Cat D. Beware.

RUNNING GEAR

Check the rear subframe bushes for excessive wear. This will have an adverse effect on handling and can be very dangerous. It’s a hugely time consuming job and beyond the reach of the amateur. Listen for a whining noise and clunking from the diff. The mounts could be perished, but more than likely it’ll be a worn diff. Replacements are easy enough to come by, but limited-slip diffs will demand a heavy premium. Check for any excess play or vagueness when changing gear. Avoid high mileage cars that jump out of gear or have worn synchromesh. Look for four matching tyres with plenty of tread. Be wary of cheap tyres which can be dangerous.

INTERIOR

Interiors are generally hard wearing, but will be past their best after 20+ years. Leather cracks over time and cloth seats will wear particularly badly on the driver’s bolster. Replacement seats are still relatively plentiful, but good quality items will command a premium, especially in leather. Switches give up the ghost with regularity, but are easily sourced and replaced. Odometers will die anytime beyond 100,000 miles as the worm gear deteriorates. Replacement gears are cheap, but fiddly to fit. Remove the card shelf from below the steering column. Any fluid dripping on this hints at a knackered clutch master cylinder. The slave should be replaced at the same time.

OUR VERDICT

The E30 is a superb car that has stood the test of time. Its styling still looks fresh while decent build quality and a growing following have ensured the survival of many cars. They also fit right in at classic shows, track days, or simply on the daily commute. Parts are cheap and plentiful and there are regular club events to attend. There really is an E30 to suit every budget, and both entry-level models and more powerful 2.5-litre cars can be affordable propositions. Many different models were produced over the eight-year production span, with varied and confusing spec sheets. Do your research to ensure you get the car to suit your needs, and don’t buy the first car you see. M3 aside, 318iS and 325i Sport models are the most desirable.

Retro cars are all the rage at the moment and the E30 is the daddy of them all. Remarkably, its boxy styling has aged well. In fact, its perfect proportions have ensured that the 3-series E30 looks as fresh today as it did when it arrived in British showrooms back in 1983.

As well as looks, the E30 has practicality in spades, which makes it a great choice if you’re in the market for a useable classic that will earn its keep. Spacious inside, the E30 will carry four adults in comfort and the cavernous boot is large enough to accommodate even the most enthusiastic of holiday packers.

A hugely practical and stylish car then, but the icing on the cake must surely be the legendary reputation for reliability that BMWs of this era enjoy. A well-maintained E30 will be among the most reliable classic cars at any show, and will devour mile after mile on twisty B-roads, motorways and everything in between. It’s the ideal daily-driver and weekend show car.

RENAULT ALPINE GTA REVIEW

A V6-powered, 2+2 sports coupé, built by a company with impeccable racing heritage – the Renault Alpine GTA made sense in any language.

The Alpine legacy dates back to 1955, when French garage owner Jean Rédélé started to produce his own sports cars based on the rearengined Renault 4CV. Evolving through the iconic A110 rally machine and the A310, the GTA was of the same Renault-engined, plastic-bodied bloodline as previous Alpines.

Thrusting the new car’s sharp-looking plastic body into the Eighties was a 160bhp 2.8 litre V6 engine, driving through a five-speed gearbox and ultra-fat tyres. Fully-independent wishbone suspension and a low-slung rear-engined chassis also charmed the motoring press at the car’s 1984 launch.

In 1985 the GTA Turbo produced an even meatier 200bhp from its 2.5 litre powerplant. A widebodied Le Mans special edition followed, before the reworked 250bhp A610 concluded it all in 1994.

VITAL STATISTICS

1986 Renault GTA V6 Turbo

Engine 2458cc V6 OHC

Power 200bhp@5750rpm

Torque 214lb ft@2500rpm

Top Speed 152mph

0-60mph 6.3sec

Gearbox 5-speed manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK

On the plus side, the outer body panels are corrosion-free polyester; on the minus side, these panels are bonded to a steel chassis frame, which was never galvanised at the Dieppe factory. As a result, rust can strike in a number of important structural areas, making corrosion checks essential for the GTA buyer.

Check the sills and jacking points, as you would for any car, but also inspect the door pillars. If the doors have dropped, it may be a sign of excessive corrosion in the A-pillars; alternatively, it could simply be down to hinge wear. If it’s an A610 you’re looking at, check the steel front floors for rust, particularly where they meet the front wheel arch liners – the earlier GTA was blessed with grot-free fibreglass floors.

Ensuring the strength and integrity of the chassis is crucial to buying a good example. For this reason, pay close attention to the suspension mounts (includingthe front and rear turrets), in addition to the rear subframe (which, fortunately, can be removed for

repair). Try to check the bulkhead where the steering rack bolts to it – corrosion can lurk here, although this is particularly difficult to spot.

The polyester-based outer panels should be less troublesome, but don’t be tempted to neglect them with your checks. If there are any cracks or splits in the plastic bumpers or front wings, then either specialist repair or replacement could be called for. New replacement panels can be found, but they’re not cheap; second-hand items can still be found, however.

The club can recommend paint specialists should re-finishing be required.

ENGINE AND TRANSMISSION

The GTA powerplants were based upon the V6 PRV (Peugeot, Renault, Volvo) engine, which powered cars from all three of these marques (as well as less mainstream machines such as Deloreans and Venturis). The upshot of utilising such a well-proven engine is that the GTA mechanicals aren’t known for any particular weaknesses, with the added bonus of having no cam-belts to change (due to the use of timing chains instead). It’s worth checking for signs of head gasket failure, though, simply due to the age of the cars.

While the non-turbo models used a 2.8 litre V6, based on the Renault 30 engine, the Turbo V6 was a 2.5 litre unit familiar to Renault 25 Turbo owners. Neither version gives particular problems, but watch out for smoke from the Turbo – blue smoke from the exhaust hints at turbocharger wear, while plenty of black smoke suggests that the unit will require urgent attention.

As with the engine, the GTA transmission has a reputation for longevity. However, watch out for any clutch judder, which could be due to oil leaking from the gearbox. Don’t under-estimate the work or cost involved in changing a worn-out clutch. The engine has

to be removed to tackle this job and while new clutch kits for the GTA can be sourced for under £200, the kit for the A610 is closer to £500.

STEERING, SUSPENSION AND BRAKES