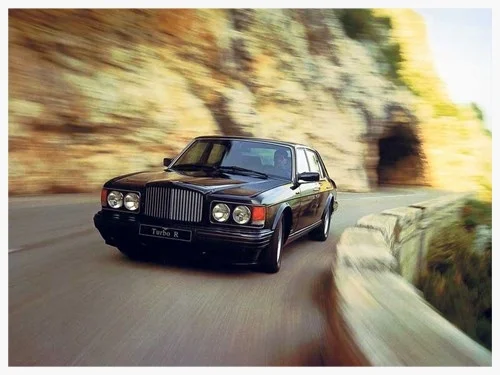

Drivers will love the Bentley T1 for its refined, laid back nature and raw power, while passengers will enjoy a standard of ride quality that few cars of the era (or any other era, for that matter) can match.

Once inside vast amounts of interior space, top quality hide and heavily engineered suspension more than make up for that, and the Bentley is one of the most comfortable cars on the road even today, delivering a soft, heavy-on-the-tyres, even roly-poly type ride.

The 6750cc V8 delivers its power in a gentle manner, but there’s plenty in reserve when you need it. The full 340lb ft of torque kicks in at just 1500rpm, so gaining speed is never an issue.

They may have more sporting pedigree than Rollers, but Bentleys like this aren’t supposed to endure hard cornering. A T1 will grip reasonably well, but the feather-light steering and equally delicate throttle and brakes don’t really lend themselves to hooligan behaviour. Slot the skinny gear selector into Drive, head for the nearest country clubhouse and enjoy the T1 as it was designed to be enjoyed.

VITAL STATISTICS

Bentley T1

Engine 6750cc/V8/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 226bhp@4300rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 340lb ft@ 1500rpm

Top speed 115mph

0-60mph 10.9sec

Consumption 14mpg

Gearbox 3-spd automatic

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Bear colour in mind when choosing a car. Colours that were popular when the car was new won’t necessarily be in vogue today and can have an impact on desirability and value. Many T1s were finished in Honey Gold and Willow Gold, but they’re not nearly as in demand as neutral blues and greens.

It’s no surprise that corrosion can be the Bentley’s biggest problem. The most common rot spots include the wing bottoms, wheelarches, sills and bumpers, none of which are cheap to put right.

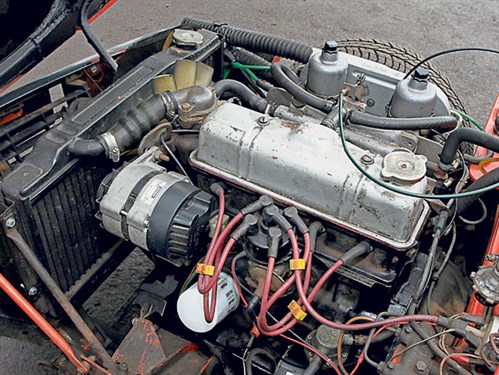

ENGINE

Low mileage cars aren’t always a good bet. If a car has next to no miles on the clock it will have been left standing for a long time. It’s better to buy one with a taller odometer reading that has been used and serviced regularly. It’s also worth finding a car that has had money spent on it – so you don’t have to.

ELECTRICS

The top-model 300SE and 300SEL had air suspension, which was high-tech stuff for the early 1960s. The ride it gives is quite remarkable, but problems can be very expensive indeed to fix, and parts are not plentiful. Buy an air-sprung Fintail with your eyes wide open, and have the phone numbers of a specialist and your bank manager close at hand.

The air conditioning system is as complicated as the anchors. It’s over-engineered as there are nine actuators to operate the upper and lower systems, so there’s an awful lot to go wrong. If it needs any work then a good specialist is unlikely to replace the whole system, because there’s simply so

much of it and it makes more sense to change the necessary parts. You’ll have to budget around £1000 for a new compressor and hoses.

The T1 is fitted with far more luxuries than most cars of its era, many of which are electrical (the windows, mirrors, air conditioning etc). Spend a bit of time inside the car and try out everything to see whether or not it works. You can bank on a big repair bill if anything is awry.

RUNNING GEAR

Gearboxes are prone to leaking, especially if the car has been standing outside for a long period. If you can, find out where the car is usually parked and inspect the ground for signs of leaks from the transmission. Early cars have a four-speed box.

BRAKES

The complex braking system is a hydraulic set-up using Citroën accumulator spheres. If the engine cuts out then the accumulators can also fail, so you could end up with no brakes. Repairs are lengthy and expensive, as the rear subframe may need to be removed. To avoid buying a dud, look for a car with as much documentation as possible and history of maintenance on the brakes.

INTERIOR

When inspecting the interior, make a point of lifting up the carpets. They’re so thick and plush that punters often don’t think to look beneath them, but they can be hiding serious water ingress and corrosion, so it’s always worth checking. Obvious as it might seem, a rotted carpet means that there are serious problems lurking beneath.

Attention to detail makes all the difference with a Bentley or

Rolls-Royce of this vintage. Tidy boots and gloveboxes, a watertight history, evidence of having been serviced by specialists and use of the correct lubricants can make a huge difference and are all signs that a previous owner has tretated the car with the necessary care and attention. A professional inspection by a specialist before you buy is also very much worthwhile.

OUR VERDICT

Few cars rival the T1 for luxury at this price other than its Rolls-Royce stablemates. But don’t be tempted by cars with rock-bottom price tags. The allure of a cheap Bentley may be strong, but it isn’t worth it unless you have double the budget for parts and you’re a dab hand with electrics, hydraulics and bodywork.

It’s been said before, but there really is no substitute when it comes to shopping around and saving up to pay more for a good car. Restored cars with a paper trail and evidence of due care and attention are worth the extra money, as it’s so easy to plough tens of thousands of pounds into a rough one. Paying a specialist a nominal fee for an inspection and getting involved with the club scene before you buy will pay dividends, too. Do it by the book and you’ll bag one of the best British prestige cars money can buy.

Raucous performance cars not your thing? Prefer to arrive at your destination in understated style, but with power to spare when it’s needed. You could buy a modern Bentley/Volkswagen for a six-figure sum – or you could set aside £10,000 (and maybe a little more) for a very tidy T1.

Essentially a re-badged Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow, the T1 differs from the Roller only in its slightly different grille and a few Bentley emblems. Inside, it’s pure prestige, with the finest of leather seats, wonderfully thick carpets and more standard equipment than just about anything of a similar era. The simple styling renders this Bentley rather subtle in appearance, but its sheer size gives it an almost regal road presence.

T1s and Silver Shadows enjoyed a lengthy production run, so there are plenty of them around. But the earliest models are now 45 years old, so time and lack of use has taken its toll on many. Budget for a cared-for car, though, and you’ll enjoy prestige classic motoring at its finest – for a fraction of what you’d pay for a modern Bentley.