Looking to buy a Triumph Dolomite Sprint? The comprehensive CCfS buying guide review will tell you all you need to know about this brilliant 16-valve performance saloon.

TRIUMPH 2000 REVIEW

Spacious and comfortable, the 2000 was deservedly popular and is still great value today...

Design work started in 1944 following Standard's wartime purchase of Triumph, with the objective of producing a saloon and sports roadster, using a common engine, gearbox and similar running gear. The 1,776cc overhead engine and gearbox which Standard had been supplying to Jaguar for their 1 1/2 litre saloon was initially employed using the existing Flying Standard rear axle. The chassis featured an all-new design which included independent front suspension and comprised of two large-diameter steel tubes joined by cross braces. With a shortage of post-war sheet steel, the main body panels were of aluminium alloy, the bodywork being styled by Standard's Frank Callaby, who included a dickey seat, similar to the design of the pre-war Dolomite Roadster coupe. Launched in March 1946 alongside the razor-edged 1800 saloon, the larger engine was introduced in 1948, featuring the 2,088cc, 3-speed gearbox together with a new rear axle, which came across from the newly-introduced Standard Vanguard. Power increased from 65 to 68bhp, raising the top speed of the Triumph 2000 from 70 to 77mph.

VITAL STATISTICS

Triumph 2000 Mk 1

Engine 1998cc/straight six/OHV

Power 90bhp@5000rpm

Torque 117 lb ft @2900

Top speed 93mph

0-60mph 13.5secs

Economy 25mpg

Gearbox 4-speed manual/3-speed automatic

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

The biggest concern with a 2000 is corrosion, and while poorer quality steel makes facelifted Mk 2 models more susceptible all will need careful checking. The sills are the first place to look as rot here can easily spread to the floor and chassis outriggers with expensive consequences. As it is, their complex three piece construction can lead to bills of £1000 per side for replacement. Blocked drain holes are a common cause of problems so check them thoroughly, especially if there’s evidence of recent bodywork repairs or restoration, and take a good look at the double-skinned front wheel arches, the door bottoms, and rear valance.

The boot floor also rots out, and it’s worth lifting the rear suit cushion if possible to check the state of the metalwork beneath. Front wing seams are another weak point and make sure you examine the A-posts and screen surrounds as repairs here are tricky and costly. Finally, take a good look at the shut lines and the alignment of the front-hinged bonnet as both are good indicators of overall condition. Finding replacement panels can be an issue although club member, Lloyd Reed, is now re-manufacturing previously unavailable items (see specialist contacts.)

The straight-six engine on the other hand is tough and reliable and should manage 100,000 miles plus before a major overhaul is needed. Replacing the canister oil filter with a screw-on type is a good move and it’s worth checking for signs of head gasket problems along with any issues affecting the crankshaft thrust washers. It’s a common Triumph problem that can lunch the engine if they drop out, so watch for excessive play at the crank pulley as the clutch is depressed. Keeping the twin Stromberg carburetors of early models in tune could be tricky and they may have been replaced with a more reliable set-up by now, but the Lucas fuel-injection on the PI shouldn’t cause trouble today – the system is well understood by specialists and should be fine if properly set up.

Noisy layshaft bearings can afflict the 4-speed manual gearbox but it’s otherwise trouble-free. And if you suspect overdrive problems – the Laycock ‘A’ unit was replaced by the ‘J’ type after 1972 – wiring problems or a low oil level may be the cause rather than anything more major. The Borg Warner automatic is strong and proves reliable with regular fluid changes. One area worth checking though is the differential as leaking oil seals could have allowed it to run dry, while the raised ride height of post-May 1974 models could lead to cracks in the subframe bracket at the nose of the diff. Lastly, listen for clonks signifying wear in propshaft and driveshaft UJs – parts aren’t expensive but replacing them all is time-consuming.

There’s not a great deal to worry about with the rest of the running gear, so it’s mainly a case of checking for wear and tear or neglected maintenance. Suspension bush replacement can be labour intensive while the rear spring top mounts can rot where they meet the inner wings and are tricky to fix. Otherwise, just watch for sloppy steering caused by worn rack mounting bushes and noisy rear wheel bearings as replacement requires the use of special tools.

Some interior trim parts are scarce now so you’ll want to make sure everything is complete, and it’s worth checking for problems with collapsing seat bases, tears in vinyl or leather trim, or damaged wood veneers. The brushed nylon seat material used later wears well though. Tired interiors can obviously be re-trimmed but the cost can soon mount so budget accordingly if things are shabby. It’s also worth checking the state of the wiring as connectors and insulation could be showing signs of age, and if the dynamo on early cars has been swapped for an alternator, so much the better.

AT THE WHEEL

The sharp Michelotti lines impressed visitors to the 1963 London Motor Show where the 2000 was launched, and the Rover P6 rival would go on to become a strong seller for the company. After the introduction of a stylish estate in 1965, buyers were offered a Mk 2 version in 1969 which brought a new dashboard design and seats amongst other changes, and then a further facelifted model in 1974. All told, around 270,000 examples were sold in total and driving one today makes it easy to see why so many people fell for its charms. The first thing you notice is just how roomy a 2000 is, and if you’re after a family-sized classic this British saloon will certainly fit the bill. And there’s always the lure of the estate if extra luggage capacity is a priority. There’s plenty of comfort on offer too, and while the improved seats and revised dashboard of the Mk 2 lift the interior ambience, all models prove excellent long distance machines. Cruising ability is certainly helped by the addition of the optional Laycock overdrive but even without it there’s decent refinement on offer, while the smooth, torquey six-cylinder engines keep things from feeling strained. The earliest models weren’t especially quick though, the 90bhp unit ensuring that 100mph remained out of reach with the 0-60mph dash taking a relaxed 13.5 seconds. Still, if you want pace you need to look to the fuel injected 2.5PI model that joined the range in 1968 which managed the same acceleration benchmark in less than 10 seconds. Smooth manual or automatic transmissions help the 2000’s easy going nature, and the rest of the controls are equally slick and well-weighted, although power steering is a useful addition if urban miles are on the cards. But whether in town or on faster roads, a well-judged ride keeps the worst intrusions at bay while the handling is safe and predicable rather than sparkling. The latter wouldn’t have bothered too many buyers at the time though and it doesn’t matter much today either in light of the big Triumph’s other attractions.

OUR VERDICT

Comfort and usability lie at the heart of the 2000’s appeal, and if family-sized classic motoring is required then look no further. Sharp styling and smooth driving manners add to the appeal, and while you need to be wary of rotten examples a solid one will be enjoyable indeed. In fact, it’s hard to think of a reason not to buy one.

TRIUMPH GT6 REVIEW

Often described as ‘the poor man’s E-type’, Triumph’s handsome GT6 is so much more than just a hardtop Spitfire

Often described as 'the poor man's E-type', Triumph's handsome GT6 is so much more than just a hardtop Spitfire. Some feel the earliest MkI looks a little over-fussy from the rear, while others were disappointed that the MkII lost the MkI's Aston Martin DB4-alike frontal styling. There are those who prefer the MkIII for its suggestion of what the tragically stillborn Stag coupé might have looked like, too. These are, however, merely degrees of separation, they're all extremely good-looking cars. Potent, too – slotting a big engine into a small car is always guaranteed to up the performance ante, but the Triumph 'six' brings with it a delicious soundtrack, too.

The GT6 ticks many boxes on the practicality front, too the tailgate lifts to reveal a good-sized luggage area; the MkIII in particular has decent interior headroom; and there's substantial parts back-up from specialists. They're easy to work on thanks to the tilt front end, too, and you don’t need to have deep pockets to buy or run one.

Style, performance, handling and practicality allied to low costs – could the Triumph GT6 be the ultimate classic?

The GT6 goes up in weight as you go through the versions, but so does the bhp, so each one feels as nippy and powerful as the others. The main difference is in the handling, the MKI handling fairly poorly whilst the suspension changes on the MKII and III ensure things are better in those reincarnations.

In terms of comfort being tall may be an issue with the MKI and II. We’re discussing a rather small vehicle in the Triumph GT6 which, although is made slightly more accommodating in the MKIII, isn’t perfect for those on the taller side. If you can bend your frame into the car into the first place the GT6 has a simple but beautiful interior which should only add to your glee as you spark up the engine.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 1998cc/6-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 104bhp@5300rp

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 117lb ft@3000rpm

Top speed 110mph

0-60mph 9.5sec

Consumption 27.9mpg

Gearbox 4-spd manual + Overdrive

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

As with any classic car, only the foolish fail to check for rust in all the usual places (wheelarches, bonnet/boot lip, sills, around/behind chrome trim etc.), but be particularly attentive around the bottom of the windscreen. If you’re looking at buying a MkI or MkII, the windscreen surround can be removed separately in its entirety if it has rotted through to the point where it cannot be saved, whereas on the MkIII, it’s an integral part of the front bulkhead pressing to allow a two-inch deeper screen and steeper rake (two elements that combine to open up much-needed interior headroom). Replacement, as such, is a much more involved job.

Staying with the rust theme, extensive corrosion in the front firewall is bad news, as this is essential to the car’s structural rigidity. While you’re on the hunt for rust, check also the transmission cover (if it’s not secured, it can allow exhaust fumes to leak dangerously into the cabin), battery box (you’ll need to remove the battery to get at it properly) and rear upper suspension mounts.

ENGINE

Sticking with the MkI, it’s worth making doubly sure that the cooling system is fighting fit. In order to get the six-cylinder engine to fit into the GT6’s engine bay, the radiator had to pushed as far forward as was physically possible, and dropped between the chassis rails, which in turn created a rather convoluted and complex cooling system. Any minor pressure loss or leaks will, therefore, be magnified ten-fold.

RUNNING GEAR

A test-drive is a must on any MkI GT6, as the handling is compromised significantly by the swing-axle rear suspension. This was lifted, lock stock and barrel from the Herald, and unless the car you’re looking at has been suitably modified by a previous owner, you need to be ready for snap lift-off oversteer in the corners. Which, depending on your point of view as a driver, is either great fun or utterly terrifying.

If the GT6 has an Achille’s Heel, it concerns the transmission. Persistent loud noises, worn synchromesh and reluctance to engage gear are all symptons that require immediate attention. One of the most common failings concerns the output shaft bearing, and while the optional Laycock overdrive is pretty bullet-proof, replacement of even just the O-rings can entail removal of the entire gearbox.

INTERIOR

If you’re anything over average height, then it’s imperative that you try before you buy. It’s not a spacious car inside by any means, so many taller owners resort to replacing the standard 15-inch steering wheel with something smaller in diameter, as well as reclining the seat much further than they usually would. Obviously, it’s best to discover that you can’t live with this sort of compromise before you part with your cash. The optional rear seats, meanwhile, are best viewed as nothing more than an additional storage area.

OUR VERDICT

Often overlooked thanks to the Spitfire’s wind-in-the-hair promise, the GT6 still has a strong following thanks to its six-pot engine and greater practicality. It’s probably also the better handling car of the two, thanks to its more rigid bodyshell.

Interestingly, too, the GT6 never really had any direct mainstream competition: the much bigger MGB GT was only ever available with a four-cylinder engine until the arrival of the short-lived and dynamically inferior MGC, and the later-still V8.

In truth, it’s hard to think of a good reason for not choosing a GT6 as a classic. Some argue that you’d have to be dead-set on a convertible to choose the Spitfire instead for similar money, since the GT6 is faster, more powerful, more practical and makes a better noise. It’s a rarer sight on the roads, too.

Still want that E-type?

TRIUMPH ACCLAIM REVIEW

The Triumph acclaim was an emergency measure for British Leyland. Michael Edwardes expected to make the company viable during the 1980s, but the new models he needed were some years away. So a deal with Honda in Japan saw a modified version of that company’s Ballade saloon being made in Britain between 1981 and 1984, and badged as a Triumph.

Triumph purists snorted in disgust at this Cowley-built saviour, but this was the most reliable car BL had at the time. It had great appeal to older owners and became the second best-selling Triumph of all time (No.1 was the Herald 1200). Sports saloon it was not, but it was strangely satisfying to drive.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Bodywork

The biggest structural problem is likely to be rust in the sills and around the rear suspension mountings. Sills were integral with the body’s monoside, and so do not exist as separate panels. Replacement will involve folding one up from sheet metal. The rear suspension problem may well be terminal on cars worth so little because of the cost of repairs.

Almost every Acclaim will have a rusty front valance, which doesn’t affect its roadworthiness but always looks a mess. Look for rust in front wings around wheelarches (new front wings can still be found) and in the same place on rear wheelarches (you’ll have to cut it out and weld new metal in).

Rust can also break out under the trim strips on the bonnet and boot. If drain holes become blocked, the closing panel at the rear of the boot will succumb, too. Top-model CD iants have chrome on bumpers, which suffers like all chrome.

Remember, though, replacement panels are virtually non-existent.

Engine

The Honda engine doesn’t give much trouble. The cambelt needs to be changed every 45,000 miles, and you’d be wise to change it as soon as you buy a car. Only after 130,000-150,000 miles does oil consumption go up noticeably, but few Acclaims have done such high mileages.

Listen for a top-end clacking noise, which is evidence of a worn camshaft. The twin Keihin carburettors may cause rough running, but the cause is often no more than a blocked idler jet. A common problem seems to be failure of the vacuum advance-and-retard mechanism on the distributor, but owners have found a way round that. You simply block off the vacuum pipe and retard the ignition a little.

The radiator fan is electric and the Acclaim isn’t particularly known for overheating. Even so, you’d be wise to make sure that the fan does work.

Running gear

Once again, most of the running-gear is long-lived, with typical Japanese standards of reliability. You get a rod-operated fivespeed manual gearbox which feels quite positive or, on HLS and CD models, a Triomatic semi-automatic. Though sold as a three-speed, it was actually a twospeed with lock-up top known as O/D. Identical to the Hondamatic, it will be no stranger to your local auto trans specialist.

The Acclaim is a light car with front-wheel drive, and hard acceleration from rest can result in torque steer. It’s a characteristic rather than a defect. More worrying is clutch judder, which can have a iety of causes. A common one is failure of the top bush on the engine torque rod, and that’s easily fixed.

Not quite running-gear is a problem with the wiper shafts, which can seize. When they do, they often pull out of line sideways, cutting into the metal of the bulkhead. Making good there can be difficult. As for replacement, some owners have adapted Ford Fiesta parts to fit.

Interior

Interiors are rather dull and plasticky, but nevertheless durable. Front carpets are likely to be the biggest issue, as they wear over time. Wet carpets should alert you to a leaky windscreen.

Most Acclaims have cloth upholstery, and that can fade if the car is kept outside in the sun. The good news is that seat covers can be removed, so a replacement set sourced from a scrap vehicle will be a viable solution. On models with the CD trim level, the upholstery is velour. It’s very 1980s but surprisingly luxurious and well worth having. CD models also have electric windows (operated from a truly horrible add-on master control panel), so it’s advisable to make sure they work properly.

While checking inside the car, examine the hardboard panels that form the boot floor. They are not very robust, and often split.

OUR VERDICT

An Acclaim can make a great starter classic, easing you into ownership of an older car for very low cost. It will be reliable enough to keep you on the road, but when things go wrong you’ll quickly learn the joys of visiting all your local scrapyards for parts.

Fellow owners will be the best guide you’ll ever have to what classic car clubs are all about.

TRIUMPH DOLOMITE REVIEW

A great sporty starter classic for surprisingly little outlay

Designed to give British buyers an alternative to sporty continental competition such as BMW’s 2002, the Dolomite replaced both the front-wheel drive 1300 and the rear-drive 1500, sticking to the latter’s layout and sharpening up the chic Michelotti styling.

Inside it offers a more comfortable twist on the compact sports saloon formula – instead of the 2002’s sturdy but dour sea of black trimmings, the Dolomite sports an airy interior brightened up by the wood door cappings and the sporty three-spoke steering wheel.

Fire it up and you’re greeted with a pleasant rasp from the exhaust, and the traditional front engine, rear-drive set up offers pleasingly neutral handling which shouldn’t get you into trouble unless you really push it.

The most sought after Dolomite of all is the 127bhp Sprint model – the first British four cylinder production car to offer sixteen valves and alloy wheels as standard to its go-faster buyers.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 1998cc/4-cyl/SOHC

Power (bhp@rpm) 127bhp@4650rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 111lb ft@5200rpm

Top speed 116mph

0-60mph 9.1sec

Consumption 25mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

There are plenty of spots for rot to take hold on a Dolomite so double check the wings, the boot floor, the sills and the rear arches for any tell-tale signs, and be prepared to haggle accordingly, depending on what you find. The good news, however, is that replacement parts are easily available, meaning that it isn’t the end of the world if there are any panels which need replacing.

The vinyl roof is one of the visual tricks Triumph employed to give the Dolomite its sporty looks, but it can also cover up corrosion. It should be completely smooth throughout, and any bubbles or dips could indicate that rust has taken hold on the metal beneath.

ENGINE

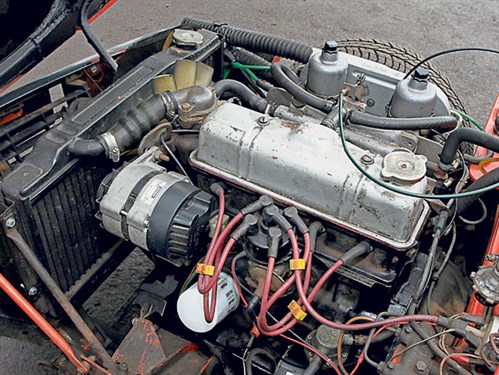

The Dolomite’s ‘Slant Four’ unit – essentially, a four-cylinder engine with the cylinders tilted at a 15-degree angle – is tried and tested Triumph technology, and a car that’s been looked after shouldn’t give you any major problems. There are two basic variants in the Dolomite range – the standard version, available in 1300cc, 1500cc and 1850cc varieties and notably used by Saab in its 99 model, and the racier 1998cc version developed for the Sprint, which uses a 16 valve cylinder head in a bid to extract extra power. Make sure to check that there’s evidence of the engine being looked after, with, for instance, a history to show it’s been serviced regularly.

RUNNING GEAR

If your Dolomite’s been fitted with the optional overdrive system, take the car for a run and make sure it’s working correctly – problems are usually related to either the relay, the wiring or there not being enough gearbox oil. Be more worried, however, if the gearbox is crunching or jumping back into neutral, which could indicate it needs a rebuild.

Dolomites should prove a sharp steer – if yours isn’t, chances are it’s down to perished bushes in the rack mounts, which are inexpensive to replace. It’s worth double checking both the front and rear suspension bushes for corrosion, both of which will show up in off-kilter handling but can be easily replaced by parts from a wealth of Triumph specialists.

INTERIOR

Rot is the Dolomite’s enemy, and if corrosion’s taken hold it may well lead to damp in the interior, particularly in the driver and passenger footwells. Make sure you lift up the footwell carpets to check for any signs of leaks or corrosion, and check the trim for any signs of water ingress.

The interior trim including those fetching wood door cappings, are generally hard wearing, but it’s well worth checking inside the car carefully for any signs of scratches, tears or marks, as interior trim and parts in good condition is usually trickier to find than many of the mechanical components. Common faults include discoloured headlining caused by exposure to sunlight – replacements can take a while to track down, while the lacquer on the woodern door cappings is prone to flaking off.

OUR VERDICT

The Triumph Dolomite offers plenty of style, charm and character and is also great value, making it a superb starter classic.

Dolomite owners are also well catered for in terms of parts and there’s a wealth of knowledge available from the various Triumph clubs, meaning there’s help at hand to deal with any mechanical maladies or bodywork issues.

TRIUMPH HERALD REVIEW

Still one of the best classics for charm, practicality and DIY simplicity...

With a maximum of 61bhp from the later 13/60, the Herald is a rather genteel, but accurate steering and a good gearchange allow you to pootle around without too much bother. Even the earliest Heralds can nudge 70mph, though 1200s introduced disc brakes, which are preferred. Refinement isn’t a huge strong point, but it’s all part of the Herald’s charm, although the high gearing doesn’t suit all tastes or driving styles. Stay away from the limits and you can corner briskly and safely. Indeed, bends can be taken quickly by employing the racing type drift corner, a technique to which the Herald adapts itself beautifully and gives absolute safety, together with a certain amount of thrill for both driver and passengers. Convertibles offer the benefit of sun-worship for four in comfort, which is a real boon on warm summer days. If you fancy a bit more go, the number of Spitfire tune-up goodies comes in handy, but consider suspension and braking modifications if you intend to boost the power output significantly.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 51cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 51bhp@5200rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 63lb ft@2600rpm

Top speed 78mph

0-60mph 25sec

Consumption 34mpg

Gearbox 4-spd manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Check for rust on the leading edge of the bonnet, the wheelarches and around the headlamps. With the bonnet open, check the bulkhead, especially around the brake and clutch fluid reservoirs. Spillage here strips the paint and allows rot to gain a foothold. The front of the chassis is usually sound, often helped by regular drips of engine oil.

ENGINE

The engines are surprisingly hardy, but watch for blue smoke and a regular knocking that suggests a worn bottom end. Be especially wary if a 1500 engine has been fitted, as they offer more power, but a weaker crankshaft. Check the engine starts well from cold and that it pulls well during a road test. Gearboxes can get noisy with age. If it all goes nice and quiet in fourth, suspect worn layshaft bearings. Watch for jumping out of gear, especially when you release the throttle after accelerating. Synchromesh can fail too – second is usually the first to go. First gear never had synchromesh. A reconditioned gearbox will set you back around £250. A wobbly gearlever might just be worn bushes – a cheap and easy fix if that’s the case.

BRAKES

The steering allows that famous turning circle of 25ft. It should be direct and free of play, so if you have to fight to keep the car in a straight line, something is probably amiss. Wear can develop in the trunnions, which need regular lubrication with a heavy oil. Ask the seller whether this is carried out and how often - every 1000 miles is the recommendation. Ideally, you should jack the car up and try to wobble the front wheels. The front suspension is simple coils and wishbones, but worn dampers will make the car very skittish and bouncy.

The rear suspension is the weak point. Pushed hard, a Herald may suffer wheel-tuck, which brings in severe oversteer. Some fit Spitfire-type swing-spring kits, but with Herald power, the chance of you upsetting the back end are fairly remote. Tired dampers can make the back end feel very unsettled, but more of an issue is a tired road spring allowing the back end to sag and upset the balance of the car.

INTERIOR

Check the state of the interior. They can get very dog-eared if neglected and are surprisingly expensive to put right. Rimmer Brothers sells complete interior re-trim kits – for doors, side panels and seats, from £1220. It also includes sound insulation, seat foam and a new headlining. Water ingress is the main issue. Tired windscreen and door seals won’t help, but nor does the bolt-together construction. A well-constructed Herald should not bang and rattle unduly on the road, so avoid ‘loose’ examples.

OUR VERDICT

The Herald is still remembered fondly as one of the best small cars built in Britain. It may have lacked sophistication compared to its rivals, but it was well conceived given the limitations forced upon Triumph at the time. The pretty coupé is rare but stylish, the convertible surprisingly practical and not too hard to find. Estates and vans are very rare – most led hard lives – but the saloon is by far the most common. Yes, you can unbolt the roof if you trust to good weather, though make sure a convertible is genuine. The rear body was stiffened on the latter, so check that any converted saloons have had the requisite adjustments made during the process.

But it’s that swing-up bonnet and sheer simplicity that are a large part of the appeal. Few classics are easier to work on. The Herald is the ultimate in Meccano-like construction, and that does little to diminish its appeal.

TRIUMPH SPITFIRE REVIEW

Pretty styling and simple mechanicals make an early Spitfire a tempting proposition, but what’s it like to buy?

Even in a fairly light car such as this, less than 70bhp from a small engine is never going to set the tarmac alight. And so it proves with the Spitfire, the 0-60mph sprint taking a leisurely 15 seconds and three-figure speeds out of reach without a (very) favourable tailwind.

What this pretty soft-top Triumph is really about, though, is fun. And fun is something the Spitfire delivers by the bucket-load. Despite what the figures might say, there is enough pep to easily keep up with modern traffic, especially if you make good use of the light and accurate gearchange.

The optional overdrive of MkII models does make longer distances a little easier, but the Spit is an easy car to row along while you just enjoy the top-down experience. Light, accurate steering is a boon around town as is the tight turning circle. The brakes are adequate but it pays not to be too exuberant in the corners, as the swing-axle rear suspension has potential to surprise in the wrong hands. It’s not as unpredictable as some would have you believe, but a modicum of caution is needed in slippery conditions.

The ride isn’t exactly cosseting – the leaf-sprung rear end making things a bit choppy (though no worse than an MG Midget) – but with the roof down and the sun out such things are easy to overlook.

What is a plus point is the snug but comfortable cabin, the low seating position giving a real impression of speed even when travelling at a modest pace. Very early cars are a bit basic, admittedly, but the few switches and dials are perfectly placed, the driving position is fundamentally sound and everything is within easy reach so you should be able to get comfortable. The MkII got better seats and carpets, by the way.

The Spitfire might lack a few creature comforts then, and refinement isn’t a strong point, but, make no mistake, it’s a very capable little sports car.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 1147cc/4-cylinder/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 67bhp@5000rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 67lb ft@3750rpm

Top speed 92mph

0-60mph 15secs

Consumption 32mpg

Gearbox 4-spd manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

The bodywork can hide a whole host of corrosion-related sins and first stop are the sills – a major structural element on the Spitfire – so problems here will seriously affect the integrity of the body. If they’ve been replaced, you need to ensure it was done correctly as failure to brace the shell can result in it twisting, so check panel gaps and door alignment carefully. The rest of the panels should also come in for scrutiny, particularly the bonnet, inner and outer wings and wheelarches, A-pillars, and front valance. Safest thing is to assume any rust bubbles are significantly worse underneath.

Replacements are common but the chassis is actually quite robust. Nevertheless, inspect it closely, paying special attention to the outriggers behind the front wheels that support the bulkhead. Rotten floorpans are common – rust can spread from flaky sills so check those too, not forgetting the suspension mountings particularly where the rear leaf spring attaches and the low points by the rear axle. Sub-standard restorations are always a risk with cars of this age, so make sure you’re happy with the car’s history and the standard of any work – putting things right can be a labour-intensive and costly process with a Spitfire.

ENGINE

Both versions used a 1147cc engine derived from the Triumph Herald’s. It’s a reliable unit and great accessibility makes it a cinch to work on. Watch for oil leaks and tired cooling systems, but the main check is for worn crankshaft thrust washers – excessive play at the pulley is the giveaway. In the worst case, they can drop out, terminally damaging the crank and block. The correct oil filter will ensure oil doesn’t drain back to the sump, leading to top-end wear on start-up, and it’s worth listening for the rumble of worn big-end bearings. It’s an easy unit to rebuild so general wear and tear isn’t a major concern.

RUNNING GEAR

The four-speed manual gearbox can suffer from worn synchromesh and whining from tired bearings. You need to check thoroughly for oil leaks, but that’s about the extent of the problems, and replacement is fairly straightforward. Overdrive was optional on the MkII so check it engages correctly – if not, it is normally electrical problems or lack of oil in the unit. Lastly, listen out for clunks from worn UJs and ensure that engine oil leaks haven’t contaminated the clutch causing slippage. MkII models got a stronger diaphragm spring clutch as part of the updates.

Easy access to the running gear means repairs are simple, but it’s worth checking a few things. The front trunnions need to be oiled with EP90, not greased, so check the seller knew that. Worn bushes and balljoints are other issues and you need to watch for sagging rear leaf springs and play in the steering rack. Don’t ignore noisy rear wheel bearings as they are tricky to fix.

INTERIOR

The cabin of an early Spit is as simple as they come, with MkII models getting better seats and carpets as standard. It’s a case of checking general condition but, with most parts available, refreshing a tired example isn’t costly. The hood on these early cars was a complex affair so check the condition of the hood and frame. A hardtop was optional on the MkII so make sure it’s not hiding a rotten soft-top.

OUR VERDICT

It may not be fast, but the styling alone should ensure it a place on your shortlist. It’s fun to drive, too. There’s a real feel-good factor to the Spitfire, and as long as you avoid the rusty ones, it makes for a great ownership proposition.

TRIUMPH STAG REVIEW

V8 power, four seats and Michelotti styling – the noble Stag has it all. We explain how to buy this handsome Brit bruiser

Unlike its Spitfire baby brother, the Stag is more GT cruiser than back road barnstormer, something that’s reflected in the multi-adjustable driving position; even the steering column can be tweaked for rake and reach. Press-on enthusiasts prefer the rarer manual/OD cars, but we reckon the auto suits the car’s relaxed demeanour rather better.

Triumph 2000 owners will feel right at home behind the wheel, since much of the cockpit furniture is very similar, but this is by no means a criticism – quite the reverse, in fact.

The 3.0-litre V8 majors on low-down torque, making it ideal for covering long distances, and it makes at least as wonderful a noise as the Rover V8 that was so often transplanted into Stags during the 1980s. It’s a bit heavier than the Rover unit, but the car leans more toward lazy oversteer when provoked than miles of dreary understeer.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 2997cc/V8/OHC

Power (bhp@rpm) 145bhp@5500rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 170lb ft@3500rpm

Top speed 112mph

0-60mph 11.85sec

Consumption 21.5mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Rust is an obvious concern – it’s a product of BL circa. 1970s, after all. Take all the usual suspects – wheelarches, inner/outer sills, floorpan – as a given for examination, but there are other, more specific areas to consider. Areas of the panel ahead of the bonnet, for instance, are in the direct firing line of thrown-up stones. The unusual swage lines above the outer headlights have vertical faces than can be tricky to repair, since they’re not easy to align with the adjacent wing and bonnet. Cheap pattern parts are to be avoided here. It’s a similar story with the panel beneath the grille/headlights, although localised repairs are easier here. Also check the front and rear top wing seams – filler is common here.

Staying on the shiny side of the car, the rear panel around the tail-lights is vulnerable to rot, likewise the lower rear valance. The leading edge of the bootlid can trap moisture beneath the chrome trim strip and rot from within, too. Bodged repairs in the A-pillar can ultimately cause those big doors to sag slightly on their hinges, so check for proper alignment within the door frame.

Moving underneath the car, the main suspect to examine up front is the vulnerable front crossmember (which is sited directly beneath the radiator – and whose lower support is also prone to rust), but it’s crucial to ensure the chassis rails and outriggers are all sound. The rear floorpan warrants particular attention, as do the subframe mountings.

ENGINE

Much has been said about the Stag’s 3.0-litre V8 engine – most of it not terribly complimentary – and while it deserved pretty much every criticism it received in period, usually for overheating, most have been sorted by now. Key to reliability is use of a coolant containing a corrosion inhibitor – failure to do so causes the alloy cylinder heads to corrode and warp and the waterways to become clogged with silt. Radiators and associated plumbing should ideally be routinely replaced every 10-12 years.

RUNNING GEAR

The V8 demands regular (every 30,000 miles) replacement of the single-roller timing chains if it is to reach 150,000 miles between rebuilds. Death rattles from this area should set alarm bells ringing, since chipped teeth or – worse – complete breakage will cause a catastrophic valves/pistons impact. Check the hydraulic timing chain tensioners, too – they rely on engine oil for lubrication, so low oil level/pressure is bad news. Wear in the shaft bearing that drives the water pump, distributor and oil pump is one likely cause of low pressure.

Transmission options are four-speed manual/OD or Borg-Warner Type 35 three-speed auto. The manual’s synchromesh will eventually wear, most likely on second and third gear, while layshaft wear is evidenced by a noisy bearing sound that disappears when you dip the clutch. Worn driveshaft universal joints will cause automatic upshifts to lurch rather than slur, although too high an idle speed can have a similar result. The diff’ is strong, but will start to whine with age. Steering and brakes are largely tough and dependable, though the former can spring leaks over time.

Trim is largely durable, and cossetted cars should be fine. In any case, much of it is still available, so a tatty interior shouldn’t be a deal-breaker on an otherwise good car. Look out for a cracked glovebox surround (where the passenger seat rests when tipped forward) or dashtop (UV damage) and baggy seats (collapsed inner foam and rubber).

OUR VERDICT

Find a sorted Stag, and you’ll be in possession of a soulful, family-friendly GT car that still turns heads – as much for its burbling V8 sound as its beautiful Italianate lines. Its impressive survival rate – allied to slowly rising values – goes to show its enduring popularity. Factor in exceptional parts backup and one of the biggest, friendliest owners clubs in the country, and the Stag’s case is complete.

CLUBS

Classic car clubs have a wealth of information about buying, maintaining and spares availabilty for their cars. Relevant clubs for this car are as follows:

Triumph Stag Register

TRIUMPH TR2 REVIEW

If it’s a classic British roadster you’re after, you cannot afford to ignore the TR2.

Said to be the cheapest British car to top 100mph, the TR2 received plenty of plaudits from road testers of the time and "fun to drive" was a regular comment. And they were right, the TR2 is just that.

Its 90bhp may not sound a lot today, but allied to compact dimensions and light kerb weight, it was more than enough to entertain an enthusiastic driver.

The cabin is a mite cramped if truth be told and the steering wheel skims the thighs of tall drivers, but ignore these foibles and the Triumph is terrific fun to throw around.

Big bumps will cause the rear end to skip around a bit but the otherwise secure handling inspires confidence. Which is more than can be said for the brakes, so a disc upgrade is a useful addition if you’re planning on regular use. A well-maintained engine should burst into life quickly and pick-up cleanly at all engine speeds, so you’ll need to investigate if this isn’t the case. But find a properly sorted example and the TR2 will prove a superb country lane entertainer.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 1991cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 90bhp@4800rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 117lb ft@3000rpm

Top speed 107mph

0-60mph 12sec

Consumption 34mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Check the wings, sills, floor panels, spare wheel well, A-posts, the bulkhead and scuttle, the boot lid, and the battery tray for corrosion. The single-skinned wings don’t tend to rust at the wheel arches, but the points at which they attach to the body vulnerable to serious rot.

Although fundamentally strong, the simple ladder chassis also demands careful attention. Rust is the first thing to look for, particularly around the suspension mounting points. Pay particular attention to the area just behind the front wishbones – if the chassis appears out of true, this is a sure sign of a prang somewhere in the car’s past. A close look at the panel gaps will also reveal any problems in this area. Lastly, watch out for poor quality restorations using cheap, reproduction panels. There are bodged cars around so ask to see the records (photographic if possible) of any refurbishment work.

ENGINE

The Standard engine is a reliable unit, and DIY-friendly too, but age and lack of maintenance will soon take their toll. Excessive exhaust smoke, rumbling main and big-end bearings, and worn tappets all point to an engine in need of a re-build, so factor this in to the asking price. Be wary of cars that have seen very little use as the wet-liner unit has a tendency to sludge-up, while the steel gasket at the bottom of the liners can rot causing oil and water to mix. The twin SU carburettor set-up rarely gives problems and overhauling them is a straightforward and fairly cheap task. Lastly, with a wide range of parts available quite a few owners tune and uprate the engine so make sure you know what’s been done on the car you’re looking at.

ELECTRICS

The top-model 300SE and 300SEL had air suspension, which was high-tech stuff for the early 1960s. The ride it gives is quite remarkable, but problems can be very expensive indeed to fix, and parts are not plentiful. Buy an air-sprung Fintail with your eyes wide open, and have the phone numbers of a specialist and your bank manager close at hand.

RUNNING GEAR

The four-speed manual geabox is a tough little unit but there a few things to watch for. There is no synchromesh on first gear, but it can wear on the other gears so this is something to check on the test drive, as are any odd noises caused by chipped gear teeth. A ‘box that is noisy in the first three gears but quiet in fourth will be in need of new layshaft owing to worn bearings – a chattering in neutral that disappears when the clutch is dipped is another sign. Overdrive was an option when new and worth seeking out for the improved driveability it brings.

The Lockheed back axle has a reputation for fragility and there is a tendency for the TR2 to break half-shafts under enthusiastic use. Oil leaks can be a common problem too. Upgrading to the later Girling unit from the TR3/3A is a worthwhile modification.

BRAKES

The drum brakes aren’t massively effective, and the drums themselves will go oval over time, so ensure the car pulls up straight on the test drive. Fitting the front disc brakes from the TR3/3A is another popular modification, as is the addition of a servo, so don’t be surprised if the car you are looking at has already been upgraded.

An independent front end with coil springs and a live beam axle with semi-elliptic springs takes care of suspension duties. Check that regular greasing has been undertaken every 1000 miles as a lack of attention will cause rapid wear. An overhaul is neither costly nor particularly difficult. Watch for wear in the steering arms and trunnions and excessive play in the worm and peg steering. A conversion to a rack-and-pinion set-up is popular.

INTERIOR

The original plastic trim is easy to replace, just check for any broken switchgear or any unsympathetic modifications that spoil the originality. Wiring that has gone brittle with age can be an issue along with weak dynamos and starter motors.

OUR VERDICT

It was Triumph boss Sir John Black’s desire to emulate the success of MG that led to the rapid design and launch of the TR2. What the company delivered was a simple, but robust little roadster. Based on a pre-WW2 Standard chassis, it borrowed the proven 2.0-litre engine from the Vanguard model, making it a quick car. Few cars are as entertaining as a classic British drop-top and the TR2 is one of the best examples of the breed, while that straightforward and sturdy construction makes it hugely tempting now.

That’s the good news. However, despite that simplicity, there’s plenty to watch out for before taking the plunge. Thanks to the healthy prices on the used market, there is plenty of temptation for untrustworthy vendors to make money from sub-standard cars. Find a good example though, and this old-school roadster will put a huge smile on your face every time you get behind the wheel. And that is surely reason enough to place the TR2 at the top of any buyer’s list.

A variety of badly maintained or poorly restored cars still find their way onto the market. Therefore a professional inspection is money well spent. Find a good one, and you’ll enjoy one of the finest little roadsters on the market.

TRIUMPH TR3 REVIEW

Alongside the contemporary MGA, the Triumph TR3 is the ‘other’ popular British roadster from the 1950s. Simple and reliable, the TR3 could reach 110 mph and sold very well to customers who – fortunately – only had performance in mind. Besides that, the TR3 offers no real comfort, and its weather equipment lets water leak inside the windscreen when the car is driven in the pouring rain. That said though, comfort is not the primary criteria you consider when purchasing a TR3. On a sunny day, being able to completely remove the sidescreens makes for an interesting driving experience too!

In period, sales climbed each successive year, peaking in 1959-60 – by which time the TR3A was the production model – at which time around 70 TRs were being built each working day. That was a remarkable figure for a sports model, and the TR3/3A range remains popular to this day. The TR3A was introduced in 1957, bringing a whole host of extras, including an optional 2.2-litre engine. The ‘A was then replaced by the much more civilised TR4 in 1961, marking the end of the side-screen era.

Driving a TR3 is an invigorating experience. The power to weight ratio is good, and the 2-litre engine is flexible enough to pull heartily from fairly low speeds. Heavy traffic can be negotiated at 20-30mph in top gear, while the car will even move off from a standing start in second gear. At the same time, it is only really above 2000rpm that the engine produces its real power.

Once on the move, the gearbox is a delight to handle, through its central stubby, short-throw lever. When the side-screens are removed there is plenty of elbow room, but space is restricted a little when they are in place. The steering itself is reasonably fast, at 2½ turns lock to lock, and includes an inch or so of free play at the rim. The ride in general is quite good. The short wheelbase and shock settings produce a certain amount of pitching over big bumps, but smaller irregularities are nicely absorbed. On the whole, the standard suspension setup offers a decent balance between ride and road-holding prowess. Post-1956 cars feature disc brakes at the front, meaning they stop pretty sharply too.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

1 The principal value of any TR is in its bodyshell, so check this both closely and carefully. Rustproofing was poor on the production line, so most survivors have been restored at least once by now. That’s ok providing the work has been done well, but unfortunately that isn’t always the case, so make sure everything lines up. If the body has been removed from the chassis at any point, it may have twisted out of true, so check all panel gaps – ideally they should be both tight and even.

The chassis should also be straight, so get the car on a ramp and have a good poke around underneath. Outriggers can rot badly, much like any of the car’s steel parts, but everything is available. Oddly enough, the bonnet and spare-wheel boot lid are the two areas least affected by rust, but check the rest of the bodywork carefully. Floorpans are particularly prone to rot.

2 TR engines are renowned for their longevity – 150,000 miles between rebuilds is possible, providing regular servicing has been undertaken. The important thing to check is oil pressure, with 50psi being the desired figure once the engine is good and warmed up. The tell-tale signs of wear are straightforward – rattling and blue smoke under acceleration. Rattling indicates the main bearings are on the way out, while blue smoke suggests worn cylinder bores and/or piston rings. Tappets can also get noisy over time, though adjustment to quell the racket is possible.

3 All side-screen TR’s used essentially the same four-speed manual gearbox. If overdrive is fitted to a TR3, it should be of the Laycock-de Normanville A-type variety, operating on second, third and fourth gears. Gearboxes are tough, but high-mileage examples will be suffering from wear. The synchromesh will give up eventually, but the first things to go are usually the layshaft bearings. If this has happened, you will hear a chattering noise at tickover in neutral, then silence when the clutch is dipped.

4 Thanks to a worm-and-peg steering setup, TR3 handling is wonderfully vintage, if a little vague. Steering box leaks are common, so if the oil level isn’t checked regularly, then rapid wear is inevitable. Lots of play means the box is worn.

5 TR3 suspension is uncomplicated and durable, though problems can occur. Chief of these is trunnion wear due to insufficient lubrication – LM grease needs to be pumped in at the front every 1000 miles. At the rear there may be broken/damaged springs or lever arm dampers, but they are a relatively cheap and simple fix. A complete suspension rebuild isn’t beyond the average home enthusiast, as the work is straightforward and costs are manageable.

6 A TR3 should be sitting on 4.5 inch wide steel wheels as standard, though wire wheels were an option. The latter have many potential issues, such as worn splines and broken, loose or just plain rusty spokes. You need to feel for play against the hubs and check for spokes that aren’t under tension. Some owners have also fitted wider TR5 and TR6 steel wheels.

7 The TR’s interior trim is simple and easily replaced if it is in poor condition. Costs will obviously add up though, so assess what needs attention and take into account what it’ll cost to put it all right. It’s much the same story with exterior trim.

OUR VERDICT

The Triumph TR series of sports cars was designed to provide maximum performance at minimum cost. Triumph found success with the TR2, so the introduction of the TR3 was a natural progression. The frontal styling change to the egg box grille was a simple change, though many more important but less obvious upgrades occurred during the TR3’s life. The engine first benefited from the high port head, then the change to 1¾-inch SU carburettors, resulting in a power boost to 100BHP.

Engineering development, assisted by the works competition programme, continued to the point where the TR was refined into arguably the most reliable, rugged and competitive sports car available in the late 1950s. To this day, the TR3 still manages to accomplish that objective in an exhilarating manner. Find a good one, and you won’t go far wrong.

TRIUMPH TR4 REVIEW

As British as they come, Triumph’s pretty TR4 is a potent and muscular sports car whose values are increasing steadily. We look at the pros and cons of buying one today

Classic Triumph TR4 Review

If you’re looking for deadly accurate steering and handling to shame an Elise, then look elsewhere: this is definitely a sports car in the old-school (1960s) sense of the word. Independent rear suspension didn’t arrive until the advent of the later (1965-67) TR4A, but the all-synchromesh gearbox (with some cars totalling seven gears, thanks to optional overdrive on second, third and fourth) and rack-and-pinion steering made the TR4 feel like a quantum leap over the preceding TR3.

It can be hustled along with aplomb on twisty country roads, that’s true, but in some ways this more an accomplished grand tourer than a screaming sportster. You really could imagine crossing countries in this car. The compact, yet comfortable cabin has it all, from the classic sprung steering wheel to the myriad dials (often sunk into an aftermarket or TR4A-style slab of polished timber). It feels more hemmed in the TR3, which used cut-down doors, but also less exposed to the elements.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 2138cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 100bhp@4600rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 127lb ft@3350rpm

Top speed 104mph

0-60mph 10.9sec

Consumption 22.5mpg

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

It’s a British car from the 1960s, so unless a prospective purchase has evidence of extensive professional restoration, there are plenty of rot spots to investigate. The separate chassis is an added complication, making it often easier to effect repairs with the body off. All the usual places corrode with the worst of them, so check the leading edges of the bonnet, bootlid and doors, windscreen surround, the tops of the rear wings, the sills, floorpan and A-pillars.

Noticeably inconsistent shutlines, particularly around the doors, should start alarm bells ringing, as chances are the root cause is a distorted chassis, either as a result of previous accident damage or a terminally rotten chassis. You really need to get the car up onto a ramp to check this properly.

ENGINE

It takes quite a bit of neglect to see off a TR4 four-cylinder engine, so keep a weather eye out for death rattles (indicating shot main bearings) and blue exhaust smoke (worn piston rings and/or cylinder bores) under load. Anything less than 60psi oil pressure is bad news, although replacing the oil pump and/or big end bearings has been known to improve matters dramatically. Chattering valve gear can often be silenced through judicious adjustment, but beware seeping oil from either the timing chain cover or rear of the crankshaft.

ELECTRICS

Electrics are of the knife-and-fork variety, and if even elementary repairs are beyond your abilities most garages will do routine work for relatively little money. Do try all the controls, however; a non-functioning heater can point to a terminally silted-up engine block, while repairing inoperative windscreen wipers is a dashboard-out job.

RUNNING GEAR

TR4 transmissions are inherently tough, but will require attention after 100,000 miles or so, specifically to the layshaft bearings. Erratic overdrive engagement can often be cured by expert adjustment. Don’t discount non-overdrive cars out of hand, either, since swapping an overdrive into a standard car is easier than you might think. Worn synchros can often soldier on for hundreds of miles with careful driving, but a re-build will probably be needed sooner rather than later. Listen for unpleasant noises accompanying take-up – the culprit is most likely one or more of the universal joints fitted to the propshaft and/or half-shaft, but it could also be a differential that’s about to part company with its mountings.

BRAKES

Many TR4s have been upgraded to modern springs and telescopic shocks by now – this is a problem only if you’re a stickler for period originality, since the original lever arm dampers were considered only average at best even when relatively new, especially on uneven road surfaces. One of the biggest TR4 headaches is poorly maintained trunnions – lack of lubrication causes them to dry out and seize, which in turn places undue stresses on the lower wishbone droplinks.

INTERIOR

Interior trim is generally hard wearing, but unrestored cars will be looking tired by now. Sagging seats – and the driver’s one in particular – are often accompanied by damaged side bolsters; a re-build and re-trim are the only viable long-term solutions. Finding a car with the much sought-after Surrey hardtop is a real bonus since prices for this factory option are very much in the ascendancy.

OUR VERDICT

Just take a look at this car and you’ll know why you want one – there’s not an iffy angle or line anywhere to be seen on Michelotti’s masterpiece, from the rounded front to the abrupt rear end. Factor in the grunty 2.1-litre ‘four’, which elicits an evocative growl from the exhaust, and there can be few finer companions on a sunny back-road blast.

It’s surprisingly practical, too (especially compared to the preceding TR3/3A) sporting a spacious cabin and a particularly accommodating boot. Certainly, you could take one on a long-haul run and not have to skimp too much on your luggage allowance.

Reassuringly uncomplicated, the TR4 sports a separate chassis and mostly bolt-on panels, which obviously makes home repairs and restoration that much easier. Triumph parts back-up is second to none, too, so if you can’t find a particular widget for your car, chances are there’s an alternative available.

Best of all, these cars can only increase in value.

The subtly upgraded, but considerably rarer TR4A tends to be the car that many buyers actively seek out – this despite the inevitable higher asking prices – but the standard car is much more readily available and good ones will have had most, if not all of their problems ironed out by now.

It’s easy to succumb to the power-mad six-cylinder charms of the later TR5/6, but while the TR4’s four-pot has a murky past (it can trace its roots back to a Ferguson tractor), it is torquey and mellifluous, and can easily be maintained by the enthusiast DIY ownera paThey are a particularly tempting medium-term investment. At the very least, you won’t lose any money; chances are your return will improve considerably.

TRIUMPH TR5 REVIEW

Combining Michelotti’s glorious lines with six-cylinder power and fuel-injection, the Triumph TR5 is arguably the pinnacle of the TR series.

Continuing the type of innovation that the TR series had become known for – the TR3 marked the first production application of front disc brakes, while the TR4A was the first quantity produced sports car in its class to benefit from independent rear suspension – the TR5 brought new-fangled petrol-injection to the masses.

Launched as a stop-gap model in 1967, it’s sixcylinder engine was basically a longer-stroke version of the Triumph 2000 unit, with most of the additional oomph coming from the PI setup, improved exhaust manifolding and a much fiercer camshaft. Power was a claimed 150bhp, achieved at 5500rpm, providing the new model with impressive levels of both grunt and performance.

Appearance wise, not a lot differed from the TR4A it replaced, with the fabulous Michelotti lines largely unfettered. The reason for this was that Triumph simply weren’t in the position to stump up for a completely retooled body, especially for such a low-volume production car. Exterior revisions were restricted to a modernised grille, matt black sills, a bright sill trim strip and prominent tail badging, including the allimportant ‘injection’ motif. Moving to the cockpit, ventilation was improved with the use of eyeball vents, while the array of switches were now concealed by a safety conscious hood.

With a purchase price of just over £1200, the TR5 was great value for money compared to many of its contemporaries; indeed, almost 3000 found homes in just over a year of production. However the improved performance wasn’t enough to mask the fact that the basic body-shell had been in the public eye since 1961 – something which was addressed in late 1968 with the following TR6.

The annals of history show the TR5 as something of a shooting star then, one that burned brightly, but not for very long.

On the road

The TR5 is anything but subtle – when you turn the key you really know about it, your ears assaulted by an aural commotion of impressive proportions. The venerable straight-six kicks into life with gusto, while a prod of the accelerator pedal yields a satisfyingly throaty rasp. The 5s weren’t known for their smoothness on tickover when new, and this one is no exception. Idling at just 600rpm, the engine is endearingly lumpy, to the extent that you almost begin to wonder if all is well under the bonnet. Thankfully it all starts to make sense once you head out onto the open road. Once that hairy cam comes on song you’re rewarded with silky smooth delivery, while there’s impressive amounts of power available from as low as 1500rpm.

Once good and warmed up, the car absolutely implores you to drive it in a determined fashion. With that celebrated 150bhp to play with, thanks to the once infamous Lucas fuel injection, it remains one quick piece of kit too. There’s more than enough grunt to press you back into the slim short-back seats as you accelerate away, the rear end squatting as all that torque explodes onto the tarmac. The IRS suspension inherited from the TR4A means it rides well too, although there’s still lashings of the scuttle shake evident with all short-chassis Triumphs. As you’re moving along the road, one thing that does strike you is just how low down you feel in comparison to everything else on the roads today. This isn’t a problem though, as the height of the doors are sufficient enough to envelop all but the tallest of drivers, giving a reassuring sense of security as you hustle along.

With a gearbox descended from the very first TR2s, the change is somewhat notchy and agricultural in nature. That’s no real criticism however; it’s precise enough and easy to get the hang of, and as long as you don’t try and rush things when a change of ratio is required, you can slot the gearlever home like a good ‘un. The rack and pinion steering feels nicely weighted, though its not the most progressive of setups it has to be said; initial understeer can turn very quickly into lairy oversteer if you put your right foot down too vigorously, especially mid-corner. Cornering ability is undoubtedly high though, despite the power oversteer, and once you become accustomed to the rather ragged progress that is at times almost forced upon you, then the 5 is great fun to drive.

No wonder then that the Triumph TR5 is one of the most sought after TRs that money can buy.

TRIUMPH TR6 REVIEW

The car that the clichéd term ‘last of the hairy-chested British sports cars’ was perhaps designed for, the TR6 has been a firm favourite for over 40 years.

The TR6 cabin experience is a snug one, particularly for six-footers, who may prefer a smaller diameter or dished steering wheel to feel more comfortable. Once you’ve settled in though, the controls fall readily enough to hand. The gearbox requires a firm touch, particularly when cold, but offers a change that is both positive and rewarding. Slotting home gears are a pleasure, especially when you make full use of the torque offered up by the sonorous straight-six engine – it’s worth holding off the changes a little longer, better to enjoy the delicious, rasping exhaust note.

If you’re aboard an original CP-series then all the better – they have that bit more urge than the CR models introduced in mid-1972, which were given a milder camshaft for smoother driving in traffic. Carburettor-fed ex-US cars are naturally down on power, but still have plenty of poke. Whatever model you go for, look forward to masses of grunt and an invigorating driving experience. Standard brakes are more than up to the task, while the independent rear suspension provides much more composed handling compared to earlier TRs equipped with live axles.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 2498cc/6-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 150bhp@5500rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 164lb ft@3500rpm

Top speed 120mph

0-60mph 8sec

Consumption 25mpg

Gearbox 4-spd manual + Overdrive

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

Start from the rear when assessing a TR6’s bodywork. Go to one corner and look down the coach line. There should be a gradual side curve from front to back. Check to see that both sides are the same. If they are not, or one side is particularly curvaceous and the other is flat, then be particularly wary. This could be down to either accident damage, or simply a poor rebuild/restoration.

Examine each of the four wing panel joints for rust, paint, bubbling or signs of local repairs. More importantly, check that the interface is visible and has not been overlaid and hidden with body filler. The rear wing/rear deck joints are particularly worth studying. You are looking for signs of soft sealer having been coated on the panel faces before the wings were bolted to the shell.

Underneath the car, run your hands along the flat of the chassis,feeling for two things – that the chassis is generally free of corrosion, but is also straight and true. Any rippling suggests accident damage. A key area to check is the ‘T-shirt’ pressing ahead of the differential. Four pieces of chassis meet there, so assess their condition thoroughly. This pressing is a highly stressed part of the chassis, as are the arms that radiate away from it carrying the trailing arm rear suspension. If repairs are required, budget on paying a professional to do the work.

ENGINE

With the six-cylinder engine, it’s vital to check the amount of crankshaft end float. With the engine switched off, lever the front crankshaft pulley backwards as hard as you can. At the same time, have someone depress the clutch pedal. If you see any movement, use a tape measure to check the extent of it. Any more than 11⁄16" or 1.5mm means attention is required.

Broadly speaking, TR6s come in home market/ROW fuel-injected specification (CP/CR), or carburettored US form (CC/CF). Only CP cars have the famed 150bhp. CR series cars, from mid-1972, were detuned for extra driveability in traffic, with only 125bhp on tap. US cars make do with a measly 104bhp. Carburettors rarely give trouble and are seen by many as being easier to maintain. Once in good condition though, the Lucas fuel injection can be made to perform very well however. Most worries stem from the overworked Lucas injection pump – replacement with a modern Bosch style item is thoroughly recommended. Check the correct engine is fitted – MG, MN, MM and MP prefixes signify a Triumph saloon unit, specifically 2.5PI, 2.5PI, 2.5TC and 2500S respectively.

RUNNING GEAR

Gearboxes are generally tough, but make sure all gears shift smoothly. A TR6 driveline features six universal joints, or UJs. Listen for clonking when taking up drive, as this generally means either the propshaft or driveshaft UJs are past their best. The rear hubs are a common malady. The bearings for them are sealed and they often fail, so be wary.

BRAKES

Other problem areas are where the trailing arms for the rear suspension and differential are attached to the chassis. Look carefully at where the trailing arms mount to the chassis. If there is rust there then you’re probably better off looking for a sounder candidate. Repairing or replacing these sections is very time and labour intensive, usually requiring a body off repair. On a test drive, listen for clunks coming from torn diff mounts – aknown weak point on these cars. A recognised – and well recommended – modification is to box in the diff’ mounts for added strength.

OUR VERDICT

The Triumph TR6 ranks as one of the most popular British sports cars ever made. Introduced in 1968 for the 1969 model year, it was basically a re-skinned TR5, complete with fuel-injected, six-cylinder engine mounted to an IRS chassis. Regular coachbuilder Giovanni Michelotti was unavailable, so German firm Karmann stepped up to the plate instead, producing a sharp redesign, but still utilising the same body tub. Both TR5 and TR6 are largely identical within the wheelbase – a nifty trick that probably saved Triumph a tidy amount of money in re-tooling at the time.

In period, more TR6s were produced than any TR before it. The last fuel-injected TR6 was made in February 1975, while production of the ‘Federal’ car staggered on in strangulated form until July 1976. When it was finally replaced by the TR7 later that year, over 94,000 examples of the ‘6 had rolled off the Canley production line. This means that there are still large amounts of survivors to choose from now, so you can afford to be quite picky in your search. On a sunny day, on a twisting A-road, you’ll struggle to beat a good TR6 for driving satisfaction.

If you are looking ahead to the summer with open-top motoring in mind, you’d do well to consider a TR6. The bare facts make a lot of sense – superb back-up from both clubs and specialists, allied to a relatively high number of cars available mean you won’t go far wrong, providing you buy a good one in the first place. The last point is particularly crucial however. For the more hard-nosed buyer, a decent TR6 will make a good investment too – the rarity and desirability of the preceding TR5 has seen prices of that model skyrocket in recent years. A knock-on effect being that the TR6 is following suit as people cotton onto the fact they are pretty much the same car underneath. Prices are nowhere near ‘5 levels yet, but have certainly strengthened over the last few years, and are sure to rise. Getting in now – at the right money of course – should prove a shrewd investment.

TRIUMPH TR7 REVIEW

Drop down into the TR7’s cabin, and most likely the first thing you’ll notice will be the immense depth of the plastic dashboard. It had to be like that to accommodate the steeply-raked windscreen that was so much a part of Harris Mann’s wedge design. However, there’s a quite cosy cockpit-like feel around the driver, and that’s a plus. But you might be surprised by how little stowage space there seems to be in the cabin.

Acceleration is adequate but not sparkling, and if you’re driving an automatic car, expect slurry rather than crisp changes. Second and third gears in the five-speed cars give a satisfying surge of power. There’s quite a satisfying rasp from the exhaust, too, although the four-cylinder engine is never going to sound as good as the six in earlier TRs – or as good as the V8 in the TR8, for that matter.

The brakes are good and responsive, and the steering OK but not especially sharp or quick. The handling in general makes a TR7 feel more like a small saloon than a real sports car, but that was the way of the 1970s.

VITAL STATISTICS

Engine 1998cc/4-cyl/OHV

Power (bhp@rpm) 105bhp@5500rpm

Torque (lb ft@rpm) 119lb ft@3500rpm

Top speed 109mph

0-60mph 9.1sec

Consumption 27mpg

Gearbox 5-spd manual

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

BODYWORK & CHASSIS

New body panels ran out years ago, but specialists have manufactured reproduction panels and repair sections. On the cosmetic side, look for rust in the front wings, front body panel, pop-up headlamp pods, and inner wheel arches at both ends.

For structural rust damage, number one check should be the sills. Examine the inside faces by peeling back the carpets, and make sure that the outer sills are proper panels and not just "cover sills"; a proper full-length sill extends behind the front wing. On convertibles, look also for rust in the boot floor, inner rear wings, and the inside of the rear quarter-panels. One area to check very carefully on both coupés and convertibles is the trailing arm mounting points.

Many fixed-head TR7s came with Webasto fabric sunroofs. These had wooden frames which can soak up water and rot through: a clue is staining on the headlining. Repairs to damaged sunroofs can be surprisingly expensive.

At the front of the car, check the windscreen frame. Rot can start under the chrome trim and affect both the lower frame and the upper, including the front edge of the roof.

ENGINE

The one mechanical problem you don’t want is an overheating engine. The alloy cylinder head corrodes, waterways clog, and the head then warps. The temperature needle should not stray past the "normal" mark.

ELECTRICS

Contrary to popular belief, the pop-up headlamps do not give a lot of trouble, although getting them to perform in fully synchronised harmony can be a job beyond even the most patient owners.

RUNNING GEAR

A four-speed gearbox was available up to 1978, and isn’t much liked. It had its origins in the Marina, and high-mileage examples will suffer from weak synchromesh and may jump out of gear on the over-run. The five-speed available from 1976 and standard from 1978 was the LT77 type that was also used in Rovers, Jaguars, Range Rovers and Land Rovers, so it’s pretty tough. Listen for a rattle under power in third gear, which usually means the fluid is low, and remember that the fluid for these gearboxes is automatic transmission fluid; using thicker ordinary gearbox oil results in baulking synchromesh and you might not get the box into second when it’s cold!

A common problem on TR7s that haven’t been used for some time is a sticking clutch. The five-speed gearbox depends on splash lubrication, so towing the car and dumping the clutch at speed might free your clutch, but it might also wreck your gearbox!

BRAKES

Finally, a steering vibration between 50 and 60mph is quite common, and can be hard to eliminate. So it need not be a deterrent to purchase unless it’s severe or there are indications of steering or road wheel damage.

OUR VERDICT

No doubt about it: the best buy for maximum fun is a late convertible, with the five-speed manual gearbox rather than the automatic option. It gives open-air motoring in a manner which is a brilliant compromise between the old manner and the modern cocooned style.

On the other hand, if you want maximum value for money and don’t really care for the open air, get the best coupé you can find. For what they offer, the cars are under-priced, and a coupé really does make sense as characterful everyday, all-weather transport.

The cost of repairs means it really isn’t worth buying a basket-case for restoration, so such cars are best considered as sources of spares only. However, if you enjoy DIY work and know what you’re doing, why not uprate to Sprint specification? You can buy all the necessary parts.

Die-hard TR fans were pretty rude about the TR7 when it was new, and it’s certainly not a hairy-chested sports car in the tradition of the TR6 it replaced. Today, though, it makes an affordable and pleasant way of getting into TR ownership, especially in convertible rather than fixed-head form. Properly maintained cars make reliable classics and can provide plenty of fun.

Once you know why you want one, the next problem is deciding which one you want. The TR7 was introduced as a fixed-head coupé in 1975 and didn’t become available as a convertible until 1979. Coupés were built until the end in 1981 but don’t have the following that the convertibles enjoy.

TR7s were built in three factories. The earliest cars were all built at Speke, by a disaffected and strike-prone workforce. They weren’t generally built well. After one strike too many, production was transferred to Canley in 1978, where quality went up by leaps and bounds. Then from 1980, TR7s were built at the Rover plant in Solihull, and some people say these were the best of the lot.

TRIUMPH VITESSE REVIEW

Upmarket cars sporting a quartet of frowning ‘Chinese Eye’ quad headlights were all the rage in the 1960s. Jensen C-V8, Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II, Bentley S3, Chrysler 300G/H – they were all at it. But surely the pleasingly aggressive-looking Triumph Vitesse is the most famous of them all. It’s remarkable to think today, then, how close the car came to never getting beyond the design stage.

Standard-Triumph may have enjoyed some glory years during the 1950s with the Triumph TR series, but as the 1960s dawned, it was clear that the company wasn’t in the greatest of financial health. In the event, it was a last-minute rescue package from Leyland Motors in 1961 that finally saved the company.

Project ‘Zobo’ – aka the Herald – went into production two years before Leyland entered the picture, but Standard-Triumph’s increasingly bleak-looking balance books suggested it wouldn’t survive for long. Plans had been in place to revive a curious and oft-maligned 1930s trend for small six-cylinder cars ever since the Herald’s inception, however, and with Leyland’s backing, the car entered development.

Ironically, the initial development hack – nicknamed the Kenilworth Dragster – packed a 2.0-litre Vanguard engine and was used by Technical Chief, Harry Webster, as his own car for several months. For production cars, however, an enlarged version of the Herald’s SC (‘Small Car’) ‘four’ was deemed more appropriate at 1600cc, with twin Solex carburetors upping power to 70bhp.

A Herald gearbox sporting tougher internals and closer ratios – but still no synchromesh on first gear – was deemed sufficient to handle the extra power, but, subtle changes to the suspension aside, the standard chassis was largely retained.

The car survived until 1966, at which point the Vitesse was upgraded with a 2.0-litre engine, stronger gearbox and better brakes, but it wasn’t until the 1968 advent of the Vitesse Mk2 that the swing-axle rear suspension was finally canned.

The factory sold 51,212 examples before it was phased out in 1971 in favour of the new Dolomite range.

VITAL STATISTICS

Triumph Vitesse 1.6

Engine 1596cc/6-cyl/OHV

Power 70bhp@5000rpm

Torque 110lb ft@2800rpm

Top speed 83mph

0-60mph 17.8sec

Economy 24.6mpg

Gearbox 4-speed manual + opt O/D

ON THE ROAD

No doubt about it: the Triumph Vitesse looks meaner than the proverbial junkyard dog just parked up on your driveway. It’s a good job, then, that it has the mouth to match the trousers, although the six-pot lurking beneath this particular car’s trademark tilt-front bonnet is the 70bhp 1600, not the later 2.0-litre mill, which mustered 95bhp.

It’s an appealing little ‘six’ nonetheless – it’s good for over 80mph in top, and while a 0-60mph time of over 17.5 seconds doesn’t sound like much to write home about, it feels much brisker in practice, not least as it weighs barely 920kg.